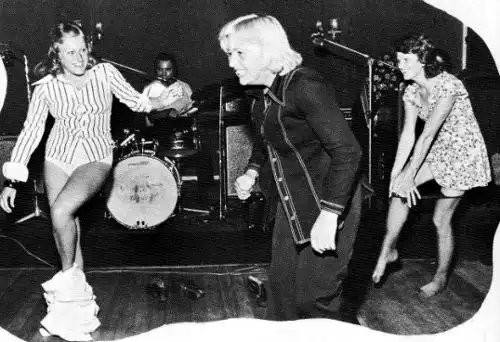

Just as in the Vietnam war, where American soldiers were entertained by visiting bunny girls performing erotic shows, much the same happened in Rhodesia. While never officially sanctioned by the authorities, it was considered important to maintain the morale of the fighting men.

These events were symptomatic of a general malaise. Striptease shows and live entertainment had become a regular feature in the operational areas by the mid-1970s.

Several enterprising Rhodesian women organised explicit live shows with the tacit connivance of the security-force authorities in the operational areas, and Zilla and Gina were familiar figures in many Rhodesian security-force camps during the mid and Iate-1970s.

The full extent of these semi-institutionalised sex-parties spawned a generation of women who were quick to cash in on a lucrative service industry.

Martine – Tina or Gina – was Zilla’s co-artiste and sometime stage partner. She, too, contributed to lifting the morale of servicemen by explicit performances. Both performers came from Rhodesian family backgrounds, but broke tradition with the conservative view of the role of the Rhodesian woman.

Geraldine Roberts, who took the stage name of Zilla, was the daughter of Hope and Dudley Roberts. While Geraldine attended Arundel School, one of the countryʼs finest institutions of learning for girls, and showed great academic promise, her career developed in another direction. Zilla, working with a python, performed strip shows at many of the front line operational areas.

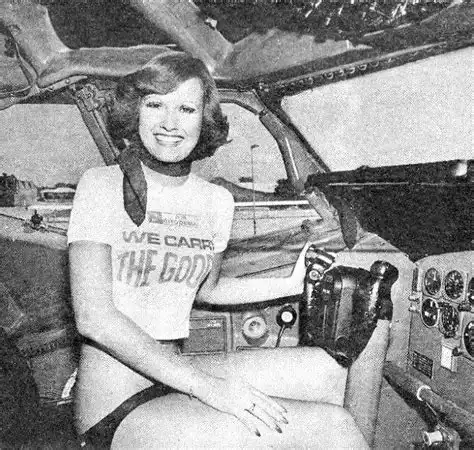

In June 1974, the two entertainers boarded a Rhodesian air force transport for the flight to Mount Darwin Forward Airfield.

The girls went through a lesbian act, supplemented by various erotic gestures and manoeuvres where the spectators were encouraged to apply body lotions or hand creams to the bodies of the scantily clad dancing girls.

These acts were performed to the languid accompaniment of sleazy striptease music played on a portable tape recorder.

Yet another indicator of promiscuity was the rise in the abortion rate being monitored by the Department of Social Welfare and the CID. Many wartime affairs ended in unwanted and embarrassing pregnancies.

Until 1975, when Mozambique closed its borders with Rhodesia, there was a well-established route to an abortion clinic in Beira. Rhodesian medical practitioners would discreetly refer patients to an address in Beira, where a Portuguese midwife ran an abortion clinic.

Many Rhodesian women flew down to Beira on Friday nights with Air Rhodesia or DETA and checked into the nearby Mozambique or Embaixador Hotel, before taking a taxi to the address in a nondescript apartment block.

When this facility was no longer available, Rhodesian women flew south to Johannesburg for similar operations. Also, during the late 1970s, there was an increase in the number of so-called dilation and curettage (D&C) operations being performed, and it was common knowledge that many of these were mere cover stories for pregnancy terminations.

Social workers counselled unmarried women to place children up for adoption after birth, but for many in the conservative Rhodesian society, the social stigma of unmarried pregnancy was unthinkable, and a quiet abortion was the best solution.

It was no surprise that, during the war years, the red-light district of the Rhodesian capital extended from its traditional limits around the Kopje area into the outskirts of the city centre and the Avenues, where prostitutes plied their trade from the streets, bars and in back rooms.

Then, a rampant increase in sexually transmitted diseases was considered a serious side-effect of this social phenomenon in the urban areas.

During the 1970s, the CID Sex and Violence section was ordered to crack down on the growing number of prostitutes. Raids were mounted on known massage parlours and hundreds of women were made to pay fines – a procedure hardly likely to halt the trade.

In the 1970s, Cecil Square became a soliciting ground for white rent boys, some of whom the police knew were still at high school. They would proposition and later assault and rob their victims in the knowledge that the incidents would not be reported.

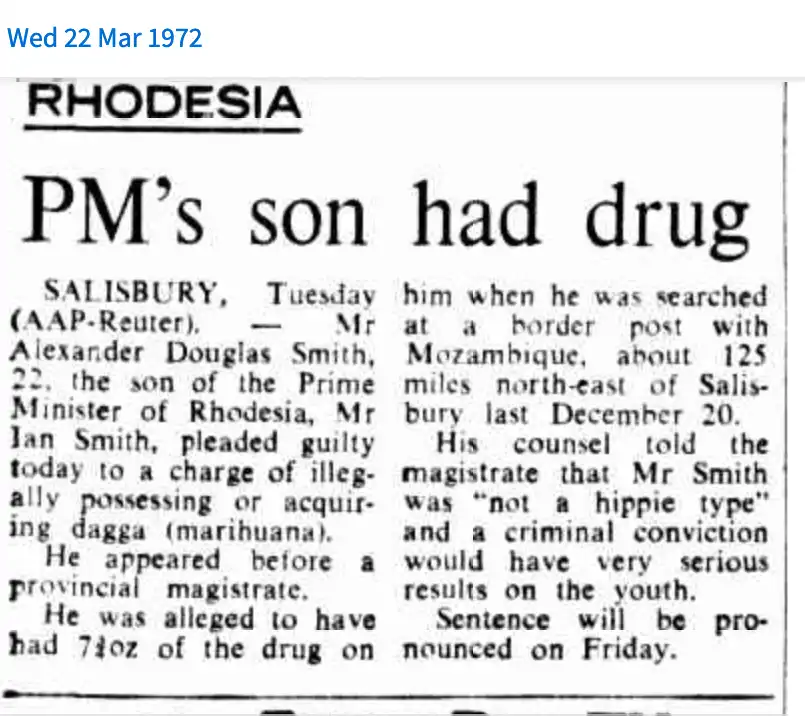

The CID drug section reported an increase in the number of young Rhodesians who travelled to Beira and Blantyre to buy cannabis, LSD and amphetamines. In the early 1970s, Alec Smith, the son of prime minister Ian Smith, imported ‘Malawi gold’ (a potent variety of cannabis) while other reports showed that he took LSD.

Yet another high profile parent to experience the anguish of drug abuse in his own family was Bishop Abel Muzorewa, whose son Philemon came to the notice of the CID after he was arrested at Marandellas, when he was found lying across the main road in an apparent suicide bid influenced by drugs.

RHODESIAN PSYCHOSIS AND THE IMPACT OF WAR

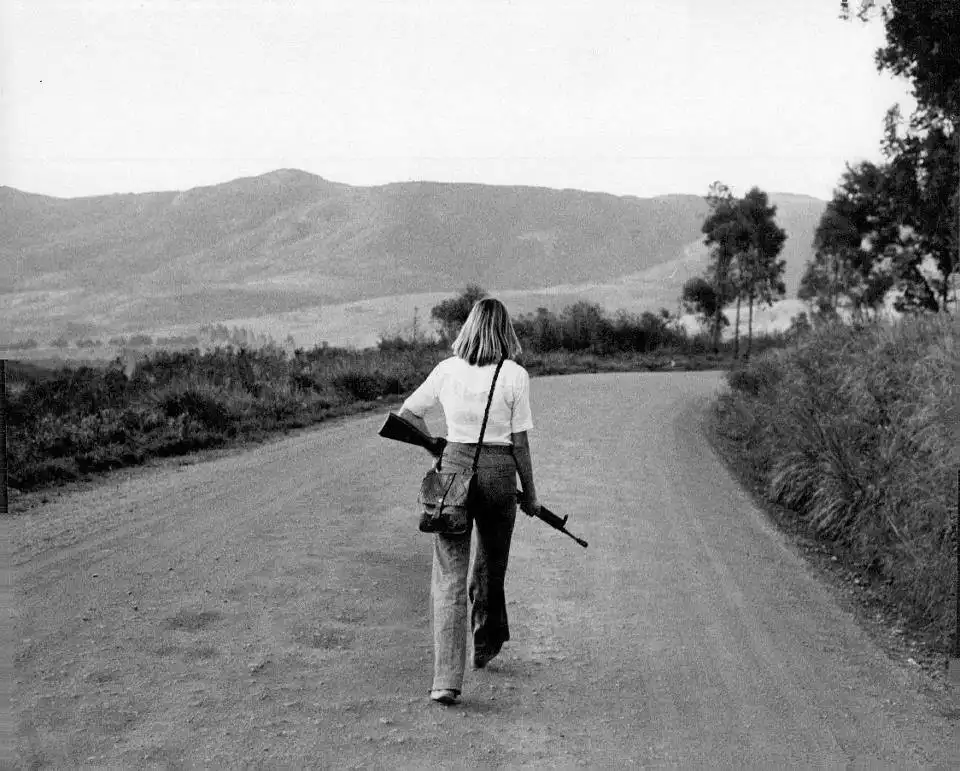

It was

perhaps inevitable that during the 1970s some Rhodesian

men and women would be affected by the very considerable

psychological pressures in their daily lives – the

guerrilla war and the ever-present danger of a sudden

ambush or landmine detonation.

Symptoms of this Rhodesian psychosis manifested itself in many ways – long before post-traumatic stress disorder had ever been heard of.

This was moral injury, a term used in the mental-health community to describe the psychological damage that service members face when they are confronted with war in their lives; many Rhodesians suffered from this.

Although the outward display of morale was high, the inner psyche for many was troubled indeed. In the aftermath of the Rhodesian civil war, few spoke of their experiences other than in terms of self-justification or, as some have expressed it, as the best time of their life.

The 1970s witnessed an unprecedented increase in the divorce rate, rising levels of illegitimate pregnancies, births and abortions, suicides and rising drug and alcohol abuse among whites. Social welfare workers diagnosed the root cause as being the pressures on white society under siege.

A key contributor to this malaise was the extended periods of call-ups and bush duty and the resultant strain on the fabric of family life. By the late 1970s, virtually every able-bodied man and women was engaged in the ʻwar effort’, which was eroding the fabric of their society, and decent Christian values were no longer quite so important as before.

A steady decline in moral behavior was noticeable after December 1972 at the Centenary police camp in north-eastern Rhodesia. In the space of a few months, this sleepy backwater police station, set in the heartland of the Centenary tobacco farming area, had been turned into a military camp where the inspector in charge exercised little control.

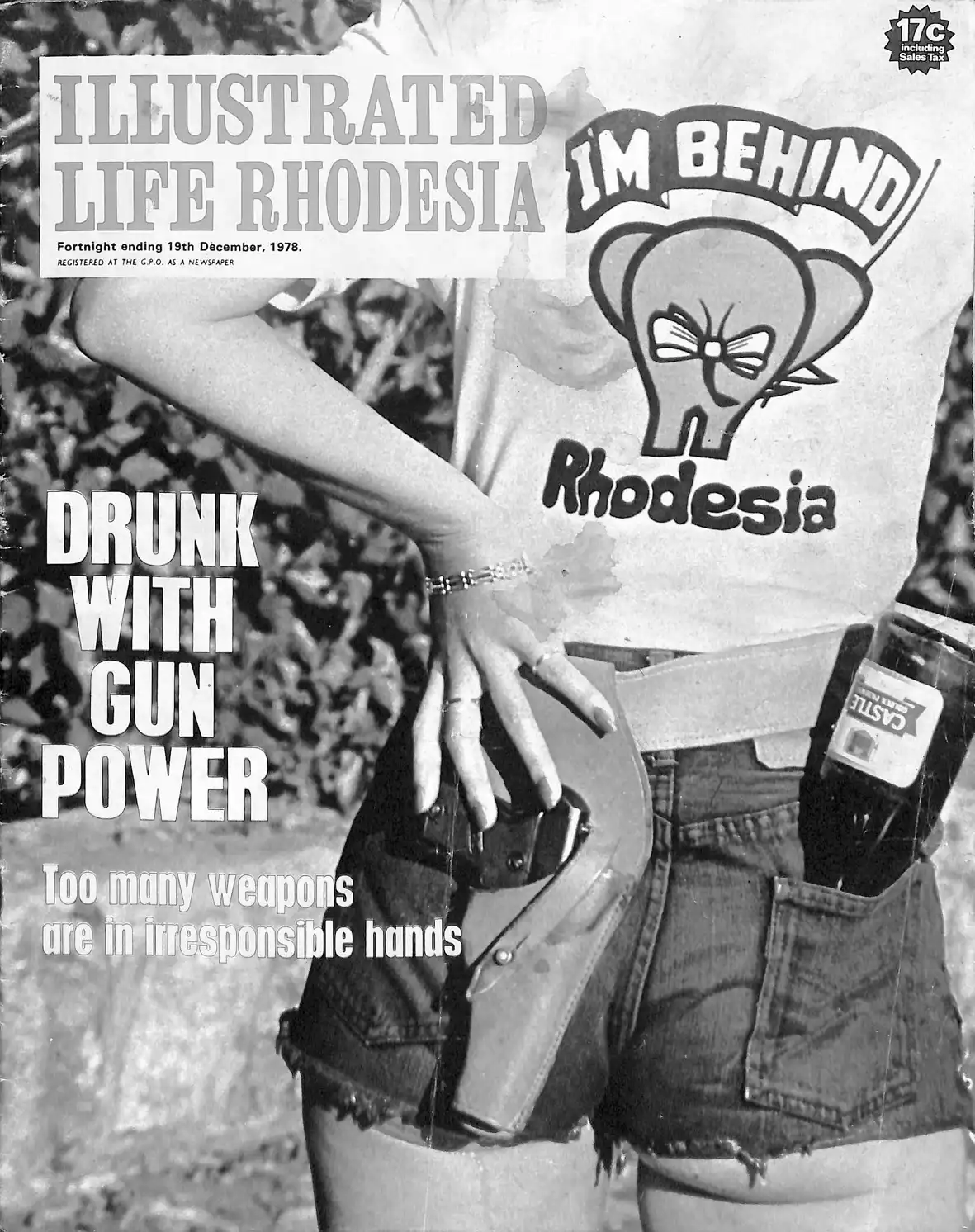

The Special Branch representative at Centenary was noted for his ability to provide a steady supply of prohibited ‘girlie’ magazines (Playboy, Penthouse, Fiesta and Hustler) to his senior colleagues. It was a common procedure that most Special Branch or CIO officers traveling outside Rhodesia would be ʻfacilitatedʼ upon their return – meaning that they passed unhindered through Customs and Immigration formalities at the airport. Many officers used this privilege to smuggle in pornography, alcohol and other goods.

Daily meetings served as a venue for the exchange of anonymous brown manila envelopes marked ʻOn Government Serviceʼ. These envelopes contained both soft and hard-core pornographic magazines, which were discreetly referred to as training manuals.

Naturally, the habit of sharing pornographic magazines spread quickly to the lower ranks. The main reason for controlling the influx of pornographic material was one of ʻprotecting Christian valuesʼ, but there was also a racial dimension, and in the late 1960s Playboy magazine was banned chiefly because of fears that blacks would see them.

At Centenary and later at Bindura, the senior officersʼ mess regularly hosted parties known as ‘grimmies‘ (as ʻgrimʼ looks did not matter if they could provide casual sex). Inevitably, the practice filtered down into the lower ranks, who made their own arrangements. Many of the women who appeared at these ʻparties’ were wives of neighbouring farmers, whose husbands were on call-up, or women who motored up from Salisbury.

Even when they were not on call-up duty, men attended Friday night security-briefing sessions, which became known as prayer meetings. ‘Prayers’ became a convenient excuse to get away from home for a good ʻpiss-upʼ and periodic strip shows. Many concerned wives wrote to army headquarters complaining about these ‘prayer meetings’, and some distraught mothers and wives wrote complaining letters to the newspapers.

As the duration of the call-up time steadily lengthened, some husbands cheated on their wives by falsely claiming to be on military service when they were with their girlfriends or mistresses. However, in the absence of their menfolk, some women openly cuckolded their husbands by seeking male companionship in the same manner.

One-night stands became a regular habit, and a favorite meeting place was the Reps Theatre bar in the Avondale suburb of Harare.

At many nightclubs, ʻladies nightʼ thrived as women banded together after work and thrilled to the acrobatics of male strippers, who would entertain until 8.00 p.m.