White society in Rhodesia was broadly defined by seniority according to the date of their family’s arrival in the territory.

The ‘old’ families, who could trace their antecedents back to those who arrived in Rhodesia with the Pioneer Column or the first treks before about 1896, saw themselves as belonging to a special class of Rhodesians.

Immigration peaked after World War II, when around 20,000 arrived annually, mostly from Britain and South Africa.

The majority were quickly absorbed into mainstream Rhodesian society and happily believed the oft-repeated claims that the white immigrants had brought peace and civilisation. As John Parker, a journalist who lived in Rhodesia from 1955 to 1965, wrote

To hear the Rhodesian tell it, the Shona people were on the verge of being eliminated by the ʻmurdering Matabele hordes’ when the just and generous white man took over and brought peace to a troubled land.

This, of course, was another of the lies that

added to a body of beliefs and myths that sought to

legitimise the white settlers’ claim to ʻbelongingʼ, for

there is no evidence of this systematic genocide.

The truth was that individual chiefs, while suffering losses of cattle and deaths, were largely able to limit the impact of these seasonal raids by dint of deal-making and traditional tribute payments, thereby retaining control of their land.

Far subtler was the insidious presence of the white man, who came upon their land by stealth and then, before they realised what had happened, assumed control and suppressed opposition by force.

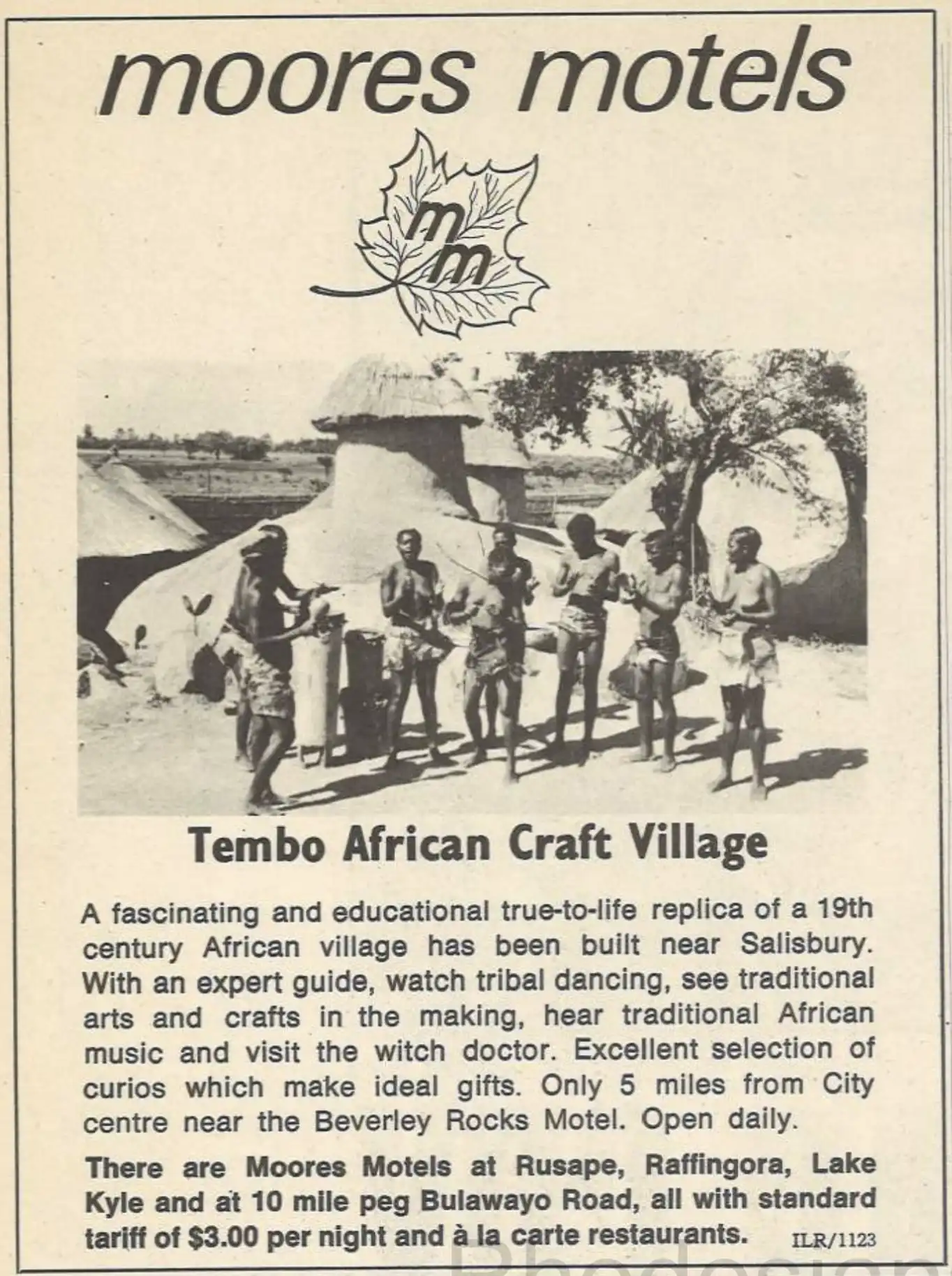

Successive generations of Rhodesians proclaimed that they were ʻwhite Africans’, but the majority resisted integration: prevailing white-settler attitudes in this ʻmaster and servant’ colonial society were deeply entrenched and, in the context of the time, integration was unthinkable.

They became a parallel society, developing a unique colonial English language and culture. Whites were far more at ease within the confines of their ring-fenced isolation. Attitudes ingrained from childhood and reinforced at school remained embedded for life.

Most white immigrants who came to Rhodesia immersed themselves in the white society, adopting the social norms and becoming Rhodesians themselves.

The settlers found it to be a bountiful land, and many prospered in one of the finest and most seductive, temperate climates in the world. And in the evenings the ʻhouseboyʼ ensured that a well-laid fire was lit in the hearth.

The country functioned extremely well in serving primarily the interests of some 250,000 whites. In the third decade after independence, it was not unusual to hear whites (and a gradually increasing number of blacks) arguing that hospitals and schools functioned efficiently under the Smith government, road and rail networks were fully maintained, and electricity and water were always available.

This was the very foundation behind the mythology of

Rhodesia, a magical land that would last for ever. In

1973, Clem Tholetʼs song, Rhodesians Never Die, became

an anthem.

The Rhodesian psyche generally

held fast to this belief, and while not all Rhodesians

believed Ian Smith’s assertion that Rhodesia had ʻthe

happiest Africans in the worldʼ, most accepted that it

was worth fighting for and simply acquiesced in the

status quo.

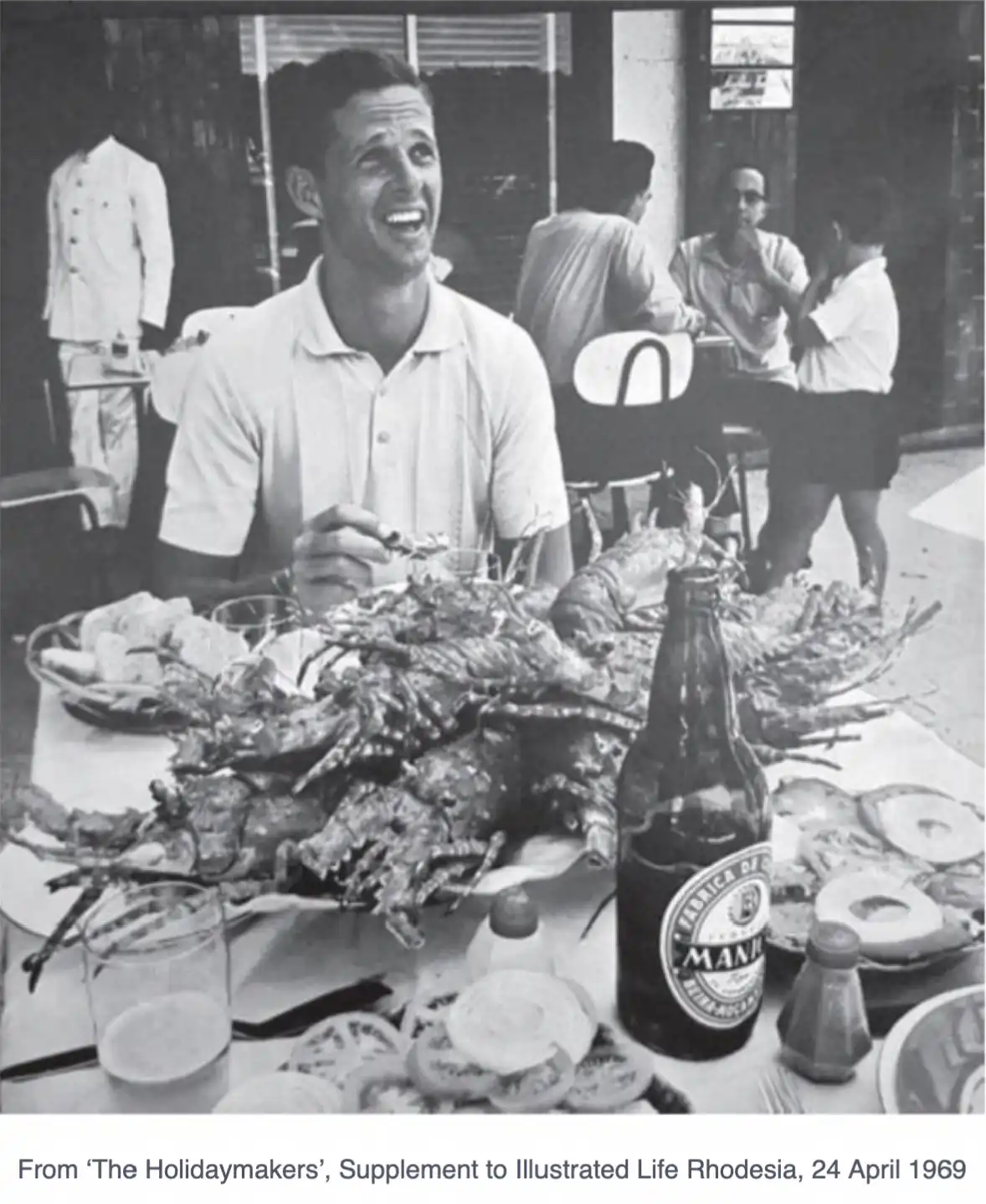

Until 1975, Beira was a top seaside destination for Rhodesians. They took to Beira not only because it was considered exotic but also because it was within easy reach.

The Rhodesians were known as beefs to the locals because of their predilection for beefsteak.

The Portuguese tolerated, but viewed with disdain the way the Rhodesian dressed inappropriately in swimsuits and often misbehaved, upsetting local society.

Rhodesians living in Umtali regularly visited the neighboring town of Vila de Manica. Manica hosted annual bullfights, which were attended by local people as well as Rhodesians, but the behavior of the latter on occasions let much to be desired. In 1956 the official service diary of the Portuguese Administrator contained the following entry

As usual the national flag was hoisted with due respect, thank heaven nothing to do with the 2,000 Rhodesian motorcyclists. As regards the bullfight, it was difficult to decide who was more brutish the bulls or the Rhodesians. They should have presented a good account of their country … I decided not to go ahead with the prize-giving nor the judging of the dancing as they [the Rhodesians], both male and female, had one pre-occupation – to drink and get drunk

Not all Portuguese were as forgiving or tolerant of the Rhodesian visitors. Young Rhodesian men would carry a demijohn of wine and during a hot afternoon become outrageously drunk and get into fist-fights with locals.

Many ended up spending a night in a Portuguese cell, nursing not only a serious hangover but also the effects of a good thrashing by the police.

BLACK PERIL

Interracial sex was considered extremely serious, and

from early on in Rhodesian legal history it was referred

to as the Black Peril. From the 1930s, police officers

investigated incidents of blacks having sex with white

women or, in some cases, merely instances of black men

allegedly lifting privy trap-doors to peer at the

buttocks of white women.

Offenders were harshly treated. It was considered unthinkable that any white woman would consent to have relations with a black man, although some did. It was far more common for white men to have sex with black women.

Miscegenation was considered ʻbeyond the paleʼ, and any police officers that took black girlfriends or married across the colour line were forced to resign – as in the case of Sergeant Charlie Sutton at Kanyemba police station who had children by Chief Mutotaʼs daughters.

Neither was it unheard of for members of the BSAP to succumb to temptation during long nights away from home. There is a verse in the BSAP regimental song ʻKum-a-Kyeʼ, which alludes to intimacy between a trooper and a black woman.

I’ve done my three in the BSAP, and that’s enough for the likes of me

1955 BSAP LP album

I’ve been on patrol so long and far away that the local girls look better by the day

I spent the night with the dirty ol’ witch, and now I’ve got a funny little itch

She was built like a house, all square and solid, and her breasts hung down like a pair of subtle wallets

She’s a big fat girl, twice the size of me with hair o’er her belly like the branches of a tree

She was standing in the kitchen, pummeling dough, and the cheeks of her ass went chuff, chuff, chuff!

She was lying there with her ass all bare and every little wiggle made the troopies all stare

I bred her standing and I bred her lying! If she had wings I’d take her flying

At a dance near London, Patrick Matimba met and fell in love with a young blonde housemaid from Holland. A short time later the two married. After returning home, he became the center of the most widely publicized racial dispute in all of Southern Rhodesia’s history.

The government found no legal way to keep Mrs Matimba out of the country. The Land Apportionment Act of 1941 forbade whites and blacks to live in the same community. At first, Patrick offered to become his own wife’s servant —the only kind of African permitted to live among Europeans.

Then Saint Faith’s Anglican Mission, in the white tobacco-growing settlement of Rusape, where his father had worked, gave Patrick a job as a £12-a-month storekeeper, and two rooms where he and his family could live. It seemed a satisfactory solution—until the whites of Rusape, many of whom migrated from South Africa, were heard from.

At a protest meeting, 350 farmers and their wives passed a resolution demanding that the government "stop this kind of thing.” When Mrs Matimba went shopping, the white ladies of the village turned their backs on her.

A tailor refused to accept her husband’s trousers for dry cleaning. When Patrick entered a bank without removing his hat, a teller ordered him out for failing to show the proper respect for white depositors.

As Rusape citizens hammered away at the government to exile the Matimbas from the area, Prime Minister Edgar Whitehead moved the second reading of an extraordinary amendment to the Land Apportionment Act, proposing that any European woman who married a native would legally become a native herself.