To justify yet another book about Rhodesia is probably more difficult than merely writing one. Hundreds of thousands of words have been written about the reasons for, the steps leading to, and the consequences of Ian Smith’s UDI.

The Rhodesian way of life has been eulogised, criticised or lambasted (depending on the standpoint of the writer) from every point of the analytical compass.

The strengths and weaknesses of the hard-line White supremacists, the middle-of-the-road men, the liberals and the Nationalists have been probed on countless occasions by writers more eminent, more knowledgeable and more intimately connected with events than I.

And yet, I have a tale to tell. It has not been told in full, and I suggest that this itself makes it of interest. But the details of the story are less important than what I hope they will show, which is how a police state could be conceived, born and nursed into full being by a community of ordinary people — “People like us.”

There is no bigger fool in the world today than a White Rhodesian. For a quarter of my lifetime to date, I was one of them, so I write not from a sense of superiority but from one of involvement.

I was there, I saw it all happening, and yet I and thousands like me did little or nothing, certainly by no means enough, to stop it.

We saw, but did not believe. We could not understand that, in the name of preserving their precious Rhodesian Way of Life, White Rhodesians themselves would systematically set about destroying the very basis upon which it was founded.

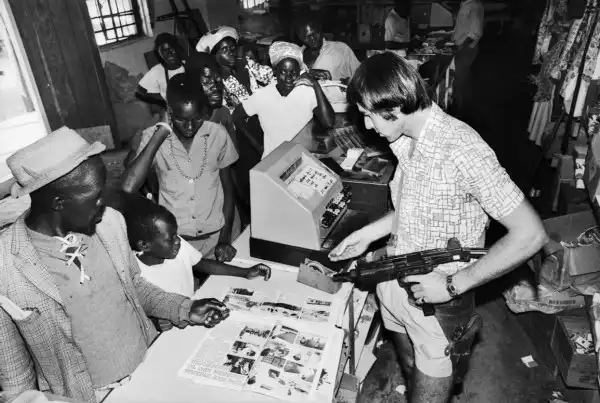

Only two days after our arrival, we acquired our first African servant — houseboy, as we quickly learned to call him. He was a smoothly good-looking man of about 30 who, to our relief, spoke excellent English and knew his job well.

We were slightly in awe of him — he was very superior and our previous experience of servants extended as far as employing the infrequent char — and he had two habits which we found strange.

The first was to spend hours every evening catching and eating — live — the great, green, locust-like grasshoppers which swarmed around the street-light outside our garden.

The second was pilfering, which was simple enough from an inexperienced couple such as us, but we learned fast enough to part company with David, for that was what he called himself, after a month.

Whether David had a wife or family, I never knew. I didn’t ask. He lived in the “kia”, as the servants quarters are known throughout Southern Africa. It simply means “room”. David’s was better than most, as we were to learn through the years.

It consisted of an unplastered brick room built on to the garage, seven feet by seven feet by seven feet, furnished by a bed with the bare minimum of steel springing and a mattress.

He brought his own blankets, cooked his own food on a primus stove provided by us (he was permitted to cook our food in our kitchen on our electric stove, but not his own) and had what were euphemistically known as “separate toilet facilities.”

This meant a cold water “shower” in a 2ft. by 2ft. box which also had a hole in the floor. Many Africans, we were told by those we felt should know, were not civilised enough to use a lavatory with a scat. They preferred to squat …

One such authority was the genial giant who was another neighbor. Like David, he also frightened us timid newcomers, although in a different way. David had been with us a couple of hours, and we were revelling in the “luxury” of being waited on for the first time, when a cheerful hail took me across to his fence.

Our new friend was well over six feet tall and burly with it. He wore khaki shorts to just above mid-thigh, and a short-sleeved shirt with pockets on the breast. Muscular tanned thighs and biceps bulged (he had played rugby for the Transvaal, I believe) and he addressed me in the guttural Afrikaans accent which it is impossible to reproduce in print.

He introduced himself.

“Just out from the old country, eh?”

“Yes.”

“Been in Africa before?”

“Not really, Egypt, for a bit …”

“Ah.

So you don’t know about Africans, then?”

“What do you mean?”

“See you’ve got a boy then.”

“Yes, we’ve got three sons, actually.”

“No, house boy. But don’t you worry. You have any

trouble with him, just bring him to me. I’m in the

African Education Department and I can hit them so the

police don’t see. Come and have a snifter.”

It would not be true to pretend that the conversation made a stronger impression on me than to leave a vague unease. For the Parker family, as for the thousands of other immigrants, the last thing to worry about was the African in Rhodesia.

He was there, convenient, irritating, smiling, insolent, hardworking or shiftless, however one found him. But he wasn’t our concern. We had no reforming zeal to improve his lot, no wish or need to meet. In fact, it was more than seven years before we entertained an African family in our own home for the first (and last) time. It is not a record we are proud of, nor for that matter particularly ashamed of.

Beyond a mild resolve to treat our servants well and, within reason, generously — which like many good resolutions we often failed to fulfil — we had no feelings at all. In those first tentative years in Bulawayo, Lobengula’s former capital, we made the groping beginnings to try to meet and know and to understand the extraordinary society which had accepted us.

Very broadly speaking, this fell into three categories. There were Pre-War Rhodesians (White); Post-War or New Rhodesians (White) and Kaffirs (Black).

There was also the twilight fringe of what is called in Rhodesia the Coloured Community (the unhappy products of miscegenation) and those members of the Moslem fraternity and their descendants from Pakistan and India who were always referred to as “Eyeshuns.”

In the category of Pre-War Rhodesians must be included of course their offspring. By and large they made up the Establishment from which were drawn the governments of the Federation and its three territories.

At the top of the Rhodesian social ladder came the Pioneers (Capital P). These were the gentlemen (and occasional lady) who had been members of the 1890 Column which first colonised the territory or possibly had arrived earlier.

Early Settlers (Capital E S) arrived between 1893 and 1896. And third down the ladder were early settlers (lower case es) who had been so fortunate as to arrive before the turn of the century. In the nature of things some 55 to 65 years later there were only a few of these venerable figures left.

Of course it is unfair to generalise, but in the main Pre-War Rhodesians tended to be rich, farmers or traders, have undistinguished offspring whom they sent (if male) to Plumtree or St. George’s, the Rhodesian Eton and Harrow.

Occasionally they turned out to be poor, feckless and living and dying in squalor in one of the corrugated iron-roofed shanties in the older roads, their minds sapped by the sun, their money sunk in cheap Cape brandy, and their habitations eaten away by white ants.

The Post-War Rhodesians were beginning to make their weight felt in society. This was the time when immigration reached its peak of 20,000 a year for a short period, and although the bulk of us came either from Britain or South Africa, there was a substantial infusion of Greeks, Italians, Germans and Scandinavians.

Rhodesia, tucked away behind its barriers of time and distance for so long, was brimming over with activity. The mood was expansion. Capital and people were flooding in, bringing with them new outlooks and novel ideas. For ten years Salisbury, once described to me by a Rhodesian as “the town where the prevailing disease is an ingrowing mind” became the cosmopolitan capital of Africa south of the Sahara.

It is strange now to recall how real it all was, when so much of it has turned out to be illusion.

The Federation, that was to bring the economic millennium to Central Africa; Partnership, under which the races would march together forward into the future, an example to the world. Both sunk almost without trace.

CENTRAL AFRICA BESET BY DOUBTS

The British tradition, so widely trumpeted, of justice and fair play, submerged almost without a struggle and re-emerging as the Nazi tradition of the Master-Race.

MORE BRITISH THAN THE BRITISH

All communities are

to some extent bound by their past; after all, the

present is founded on it. White Rhodesians, Old and New,

are swathed to the eyebrows with their history, perhaps

because there is not much of it.

In 1967, two years after UDI, a television executive in Rhodesia who had left in disgust to live in London received a letter from his former boss in Salisbury. It offered him a job better than his old one, at vastly enhanced salary, and went on: “What we are trying to do here now is to re-create the Rhodesia of the 1920s and ’30s. I am sure we will succeed, and I am sure you are the man to help us do so.”

Apart from the attitude of facing what is to come with your eyes firmly fixed on what may have happened forty years ago, the remarkable thing about this letter is that it was written by a man who himself became a Rhodesian only in 1960!

There is no reason to doubt his sincerity. But the fact remains that in 1970, three years after writing the letter, its author himself was back in London, looking for a job. Perhaps he found the task of re-creating the past beyond him.

The point about Rhodesia and its past is that, since the day that Cecil Rhodes’s emissaries persuaded King Lobengula to sign the Rudd Concession, permitting the white man to mine for gold and other minerals, Rhodesia has been living a lie.

The white man originally took control of the country by a trick, and ever since then has indulged in any number of historical self-deceptions designed to perpetuate the supremacy of white over black, the myth by which Rhodesia has lived since 1890.

Any white Rhodesian will tell you that the African has contributed nothing to the advancement of himself, or the world, through the centuries. Before the white man came to Rhodesia, you can be sure, Matabele were slaughtering Mashona by the thousand, and the white man’s only purpose was to pacify the country so that he could mine it.

To hear the Rhodesian tell it, the Mashona people were on the verge of being eliminated by the “murdering Matabele hordes” when the just and generous white man took over and brought peace to a troubled land.

Since then, the white man’s skills and the white man’s taxes have added prosperity to peace, and now, eighty years later, there are five million Africans where once they scarce numbered half a million.

Before the white man came to Rhodesia the country was mainly populated by two tribes. The larger and longer-established were the Mashona, who occupied the land for centuries and whose ancestors built the medieval fortress near Fort Victoria now known as Zimbabwe.

It is now generally accepted that these fascinating ruins form concrete evidence that hundreds of years ago the Africans of the center of the continent organised and ran their own complex civilisation. The golden empire of Monomotapa may well have been the source of the untold riches of the Queen of Sheba.

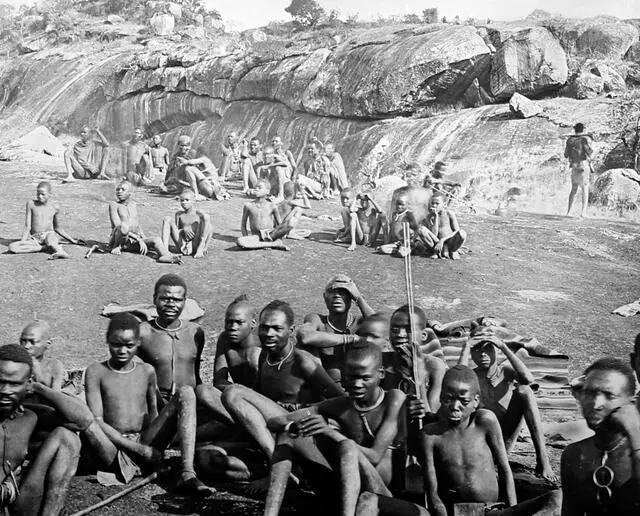

Whatever the glories of their past, the Mashona in the late nineteenth century had fallen upon hard times. They were totally dominated by their less numerous but much tougher neighbors, the Matabele. These warriors, offshoots of the Zulu nation, swept north in the first half of the century.

Their chief, Mzilikazi, had incurred the disfavour of Chaka, the great king who had knit the disjointed Bantu tribes of South Africa into a national unit.

After brushing with the Boers, at the time themselves occupied with their “treks” north from the Cape, Mzilikazi settled with his warriors in what is now known as Matabeleland, and, true to his custom, proceeded to subjugate his neighbors the Mashona, a mild and inoffensive people.

Their villages were subject to periodic raiding by Matabele impis, their women and their cattle were carried off and their young men killed.

Horrific as this practice sounds, there is no evidence whatsoever that the Mashona were being subjected to systematic genocide, as the modern white Rhodesian would have you believe.

There is more evidence to suggest that the Mashona were prepared to submit to the occasional raids by the forces of a dominant chief like Lobengula than they were the subtle and insidious presence of the white man, who came upon their land by stealth and then, before they realised what had happened, assumed control and suppressed opposition by force.

The Occupation of Rhodesia has been fully documented elsewhere many times, but it is necessary at least to sketch in the outlines of what Rhodesians regard as their propitious beginnings.

Nineteenth-century Africa was dominated by the discovery of diamonds at Kimberley and gold on the Rand in Transvaal. These in turn were themselves dominated by Cecil John Rhodes, the son of an English country parson and the least likely of all men to achieve greatness.

At the age of 17 he went to Africa for the sake of his health. He had weak lungs, and indeed these were to kill him before he reached fifty. But the sickly boy outmanoeuvred the Victorian moguls and the adventurers who flocked from all over the world to share in the new wealth.

He amassed a tremendous fortune himself, became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, and founded the Chartered Company to further his dream of spreading the British flag north to the Mediterranean.

The history of Rhodes’s machinations to obtain the Rudd Concession from the Matabele King Lobengula makes sad reading.

Robert Moffatt, a Scottish missionary, had won the friendship and confidence of Mzilikazi, Lobengula’s father, and Rhodes with cool calculation sent Moffatt’s son John, following in his father’s evangelistic footsteps, to the court of Lobengula to trade on his father’s trust.

It was not quite like shooting a sitting rabbit, for Lobengula, primitive and uneducated though he was, was a crafty ruler who foresaw pretty clearly the menace of the white man’s advance.

Moffatt persuaded Lobengula to repudiate a tentative

agreement he had signed previously with the Boers of the

Transvaal, and to put his thumb-print instead on a

mutual protection treaty with the British.

The

subsequent protection that the invading British columns

received from Lobengula was considerable. In return,

Lobengula was first tricked into allowing the white

columns within his territory, next his brave young men

were slaughtered by the Maxim gun, and finally his

capital was surrounded and he himself forced to flee

into the bush to die.

Rhodes’s “protection” would seem to have served as an excellent model for the latter-day excesses of the Mafiosa.

After the missionaries, Rhodes sent in the businessmen. With Moffatt and another missionary, C.D. Helm (also paid by Rhodes) advising him and certifying his character, Rhodes’s agent C.D. Rudd, obtained the famous piece of paper which assigned him “and his heirs and successors” the right to mine for metals and minerals.

Rhodesians have always been conscious that the pen, indeed, can be mightier than the sword. Rhodes promptly persuaded the British Government that Rudd’s document was his charter to occupy Lobengula’s empire.

Britain’s policy at the time was Imperialistic and she had no intention of being left behind when it came to sharing the spoils of the great African carve-up. Rhodes got his backing, and the Chartered Company was born.

It was of course the promise of Mashonaland’s gold which attracted investors to the Company. And it was a precisely similar promise which Rhodes held out to the 700 motley individuals he recruited to form the Pioneer Column which finally settled on the site of what is now Salisbury in 1890.

It is perhaps significant that Rhodesia’s road has been littered with broken promises of one sort or another since the very beginning. Lobengula thought he was signing way the right of a few men to dig holes in the ground; the Pioneers believed they were destined to make fortunes in return for a slightly risky few months’ ride.

The Chartered Company’s investors were led to believe

their millions would reap billions and burnish the

lustre of the British Crown. Lobengula lost his

warriors, his cattle, his kingdom and his life.

The

Pioneers made hardly a golden sovereign to rub between

them; it was not until modern machinery and methods

could be imported years later that anyone earned more

than a few shillings out of Rhodesia’s gold, and then

most of it was found under the ancient workings of the

despised Africans.

Rhodes’s Company failed to pay a dividend for over thirty years, which must have pleased the investors no end; and far from bringing honor to the British Crown the Rhodesian adventure culminated seventy-odd years later in messy and idiotic rebellion.

Occupation Day is a solemn occasion in white Rhodesia — a day of martial music, flagpole ceremonies and special prayers under the jacaranda trees of Salisbury’s Cecil Square.

For the Pioneers who drove the first Column through Lobengula’s kingdom to make laager under the lee of Harare Kopje are the recipients of a kind of reverence they neither deserved or would have expected.

The Column consisted of 200 volunteers recruited in South Africa from more than 2,000 applicants tempted by the offer of 3,000 acres of land and 15 free mining claims apiece. With them went an “escort” of 500 “police”, who would today be described as mercenaries.

Organised under regular military officers and on military lines, the Escort contained as extraordinary a mixture of adventurers as ever got together under a pirate’s flag.

Indeed, the whole expedition had something of the piratical about it.

Looking back now, perhaps the most surprising of all their achievements was that they stayed long enough to establish the community that Rhodes was banking on as his outpost of Empire.

That they arrived at all was largely due to the forbearance of Lobengula, who stubbornly resisted the wishes of his impis to attack the white man.

So as not to provoke an open confrontation with the warriors who had faced and beaten British troops only a few years before in open battle, the Column skirted Lobengula’s strongholds in Matabeleland and, led by the white hunter Selous, headed for the high veld of Mashonaland.

There was no resistance from the Mashonas, already cowed into subservience by the Matabele raiders, and indeed it seems likely that some of the Mashona tribe at first welcomed the white man’s guns as protection against the long spears of the Matabele.

Once he was in, however, the white man proved impossible to dislodge. Settlements were quickly established as the miners spread themselves around, looking for gold, and the farmers began carving a livelihood out of the fertile bush.

Quickly the Mashonas found themselves the unknowing victims of the white man’s cash economy.

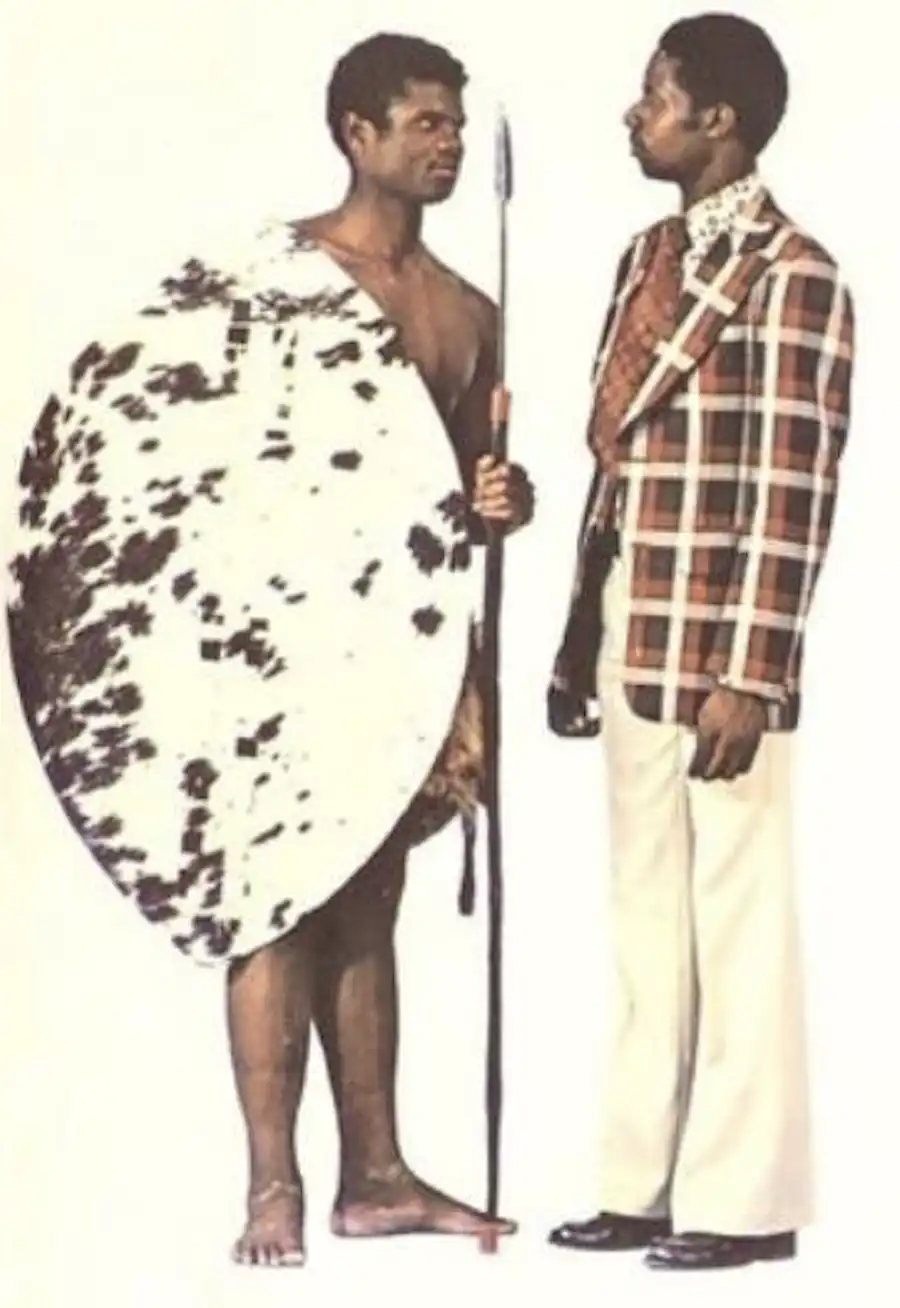

Oversimplified, it went like this. The white man wanted (and needed) the African’s labour in order to dig his mine or work his land. But the African, accustomed to centuries of subsistence farming, had no desire (or need) to work for a living.

Without putting too fine a point on it, if the white man was not to press the black into direct slavery, which would have been hardly possible or politic even in the 1890s, then he had to create in the black both the desire and the need for money.

The white man’s luxuries, his guns, his liquor, his way of life, could only be purchased for hard cash. The Mashona had nothing to sell except their labor.

But there was something else, too. The Charter granted by the British Government authorised the Company to set up an administration to run the new territories. The Administration needed cash on which to run itself, so it promptly imposed taxes on all those living in the area over which it claimed authority.

Not very much indeed — just a few shillings a head each year — but so the African was forced into the white man’s employ in order to pay the white man’s tax. So the cycle was complete, and in all basic principles has remained so ever since.

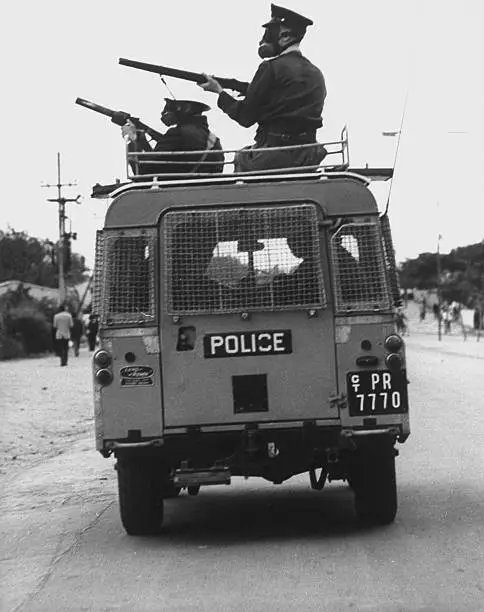

One of the proudest boasts of White Rhodesia is that, until the riots in Salisbury and Bulawayo in 1960, not a single life had been taken by the internal security forces. The lessons meted out in response to the Matebele and Mashona “rebellions” in 1893 and 1896 were strong ones indeed.

It suits modern Rhodesians to refer to both events as “rebellions”. In fact, the 1893 affair was the inevitable ultimate clash between Lobengula and the white intruders that he had postponed by his forbearance three years before.

In spite of the establishment of the white communities of Salisbury, Fort Victoria and other places, Lobengula still claimed for his impis the right to raid the Mashona.

This they did, by and large leaving the whites alone. Mashonaland’s first Administrator, Dr Jameson, believed firmly that the white man would never be secure in Rhodesia until Lobengula’s power was broken and the Company’s rule extended to cover Matebeleland as well.

He had no compunction at using the periodic Matabele raids to force a showdown with Lobengula and using his light artillery and the Maxim gun to mow down the impis at long range.

Many of the Matabele had never faced gunfire before and some of them showed fanatical bravery in the face of devastating firepower. Lobengula burned down his headquarters and fled, having first with remarkable tolerance ensured the safety of the white traders who had been trapped with him.

Lobengula was reputed to have taken with him in his flight the bulk of his treasure and it appears to have been this fact, rather than any pressing military necessity, that tempted Major Allan Wilson and his Patrol of 33 men to venture after them into the thick bush near the Shangani River.

They died to a man, and it was their fate which has inspired the most lasting and remarkable Rhodesian legend of all. Their remains lie under the wide skies at World’s View, in the Matopos Hills, not thirty yards from the bones of Cecil Rhodes himself.

It is not too far from the truth to suggest that in white Rhodesia’s hierarchy of religious idols, God comes 35th, although not one Rhodesian in a thousand could repeat the name of a single member of the Patrol.

The Matebele were defeated with very heavy losses. Some reports put the number at 5,000 tribesmen slain. What is certain is that, apart from Major Wilson’s ill-fated Patrol, white losses were extremely small.

This was far from the case in the totally unexpected Mashona uprising which followed some three years later.

This was largely inspired by the Mlimo priests, whose influence had grown sharply since the defeat of the Matabele. It was the first example of Rhodesia’s Africans combining in a genuine national movement to try to be rid of the white man’s yoke, and the lessons learned then have weighed heavily on Rhodesia’s history ever since.

In the first place, the uprising was far less gentlemanly from the white man’s point of view. This time there was no casual massacre of the valiant savage at long range from behind the comfortable sights of a Maxim gun.

Death came in the night, by the knife and the panga, to women and children as well as men, and more than one-tenth of the 4,000 Europeans then in the Colony died in the first month or two of the fighting.

The rebellion caught the whites at precisely the wrong time. Dr Jameson had denuded Rhodesia of both men and horses to take part in the ill-fated Jameson Raid on the Rand.

Militarily, the result in retrospect was never in doubt. The white men grouped themselves for the last time into their famous Boer-type laagers in Salisbury and Bulawayo and other white centres, and waited for help from the South in the form of Imperial troops. This was readily forthcoming, but it took more than 18 months before Rhodesia was pacified.

This was the last time for many years that Rhodesia made World (or even British) headlines. After the first turbulent decade, the country settled down at the dawn of the new century to some fifty years of steady, if unspectacular development.

Rhodes died in 1902, and the descriptions of his death and the last rites in the Matopos Hills filled many columns of the Bulawayo Chronicle.

His body was brought from Cape Town on the new railway, which only five years before had been pushed across the scrub of Bechuanaland to Bulawayo, and which had extended north to the copper mines of what is now Zambia and east to Salisbury.

The troubles of the Anglo-South African War passed Rhodesia by, just as the convulsions of the First World War left her virtually unscathed. By now the ingredients of the Rhodesian tragedy had been sown and were well and truly rooted.

The white assumption of supremacy had immigrated with the Columns from South Africa. Many of the early settlers were Boers, who brought their fiery puritanism and blinkered paternalism along with their hausfraus.

To the white man, the defeat of the tribes had given added proof, if such were needed, of his supremacy. But the atrocities committed by both sides in the fighting were never forgotten, even 70 years later.

After the Mashona Rebellion had been subdued, the white man settled in as the master and the African settled down as the servant. A trusted and liked servant, perhaps, and usually not a slave, but still a servant.

The arrogance of the white Rhodesian and the servility of the black between the wars is no doubt galling to the moralist and shame-making to the nationalist, but they were facts of the time just the same.