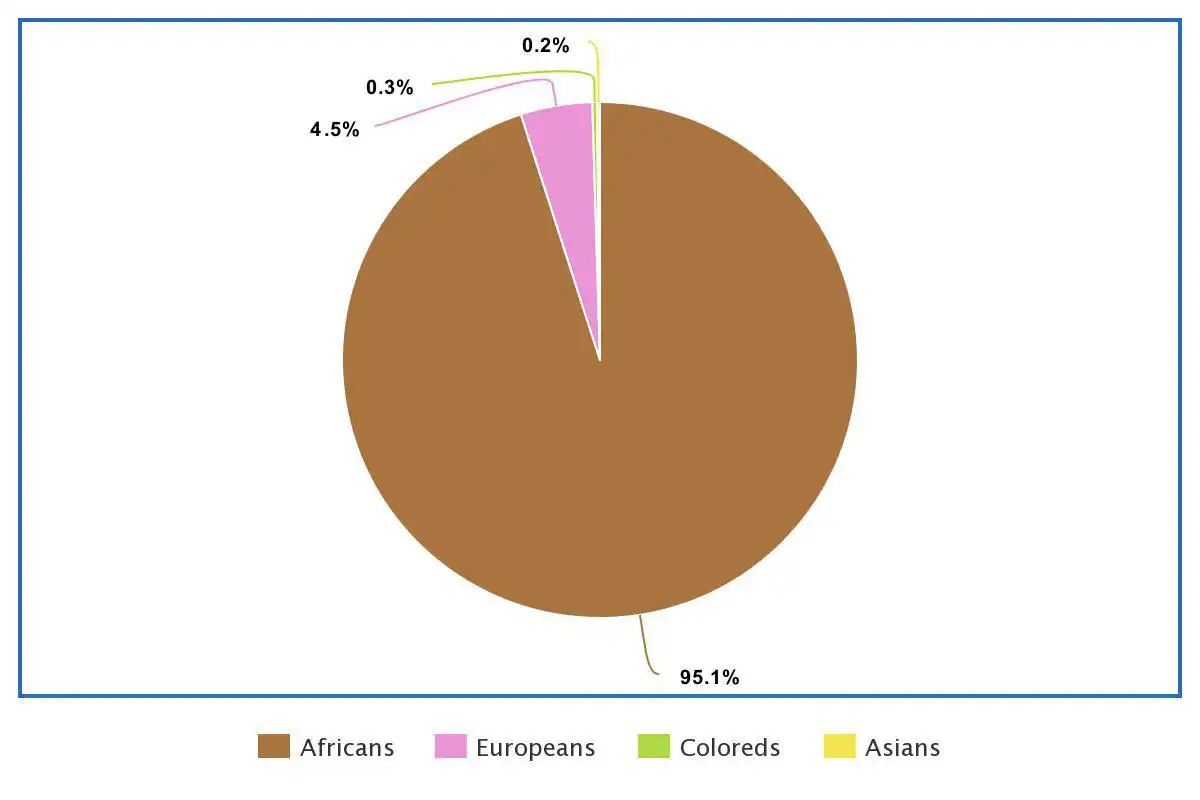

According to the official census there were 228,296 Europeans, 15,153 Coloreds and 8,965 Asians in Rhodesia on 20 March 1969. The separate African census counted 4,846,930 people.

The Shona constituted about four-fifths of the African population, and Ndebele and Kalanga made up the rest. Overall the blacks outnumbered the whites by 21 to 1

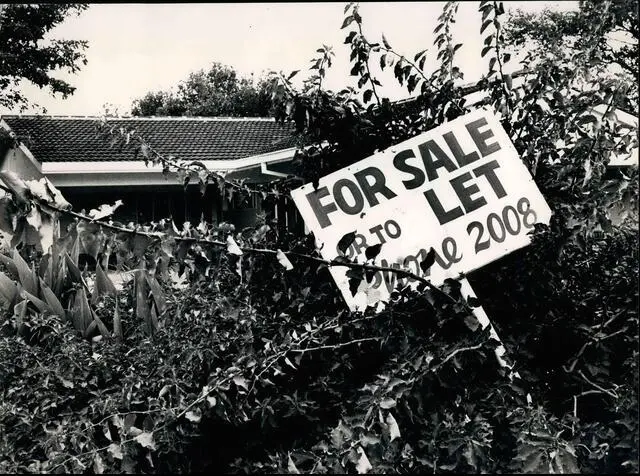

Since almost half the white population had entered the country since the Second World War, their Rhodesian roots went no deeper than 25 years. The statistical evidence raises questions about the extent and depth of the commitment to Rhodesia. From 1961 to 1969 49,987 white immigrants entered Rhodesia and 92,180 departed.

This disturbing rate of emigration suggested a vote of no confidence in the country’s future as a white ruled state. Founded only in 1890, and populated mainly by recent arrivals, white Rhodesia had to look beyond history to manufacture a Rhodesian-ness.

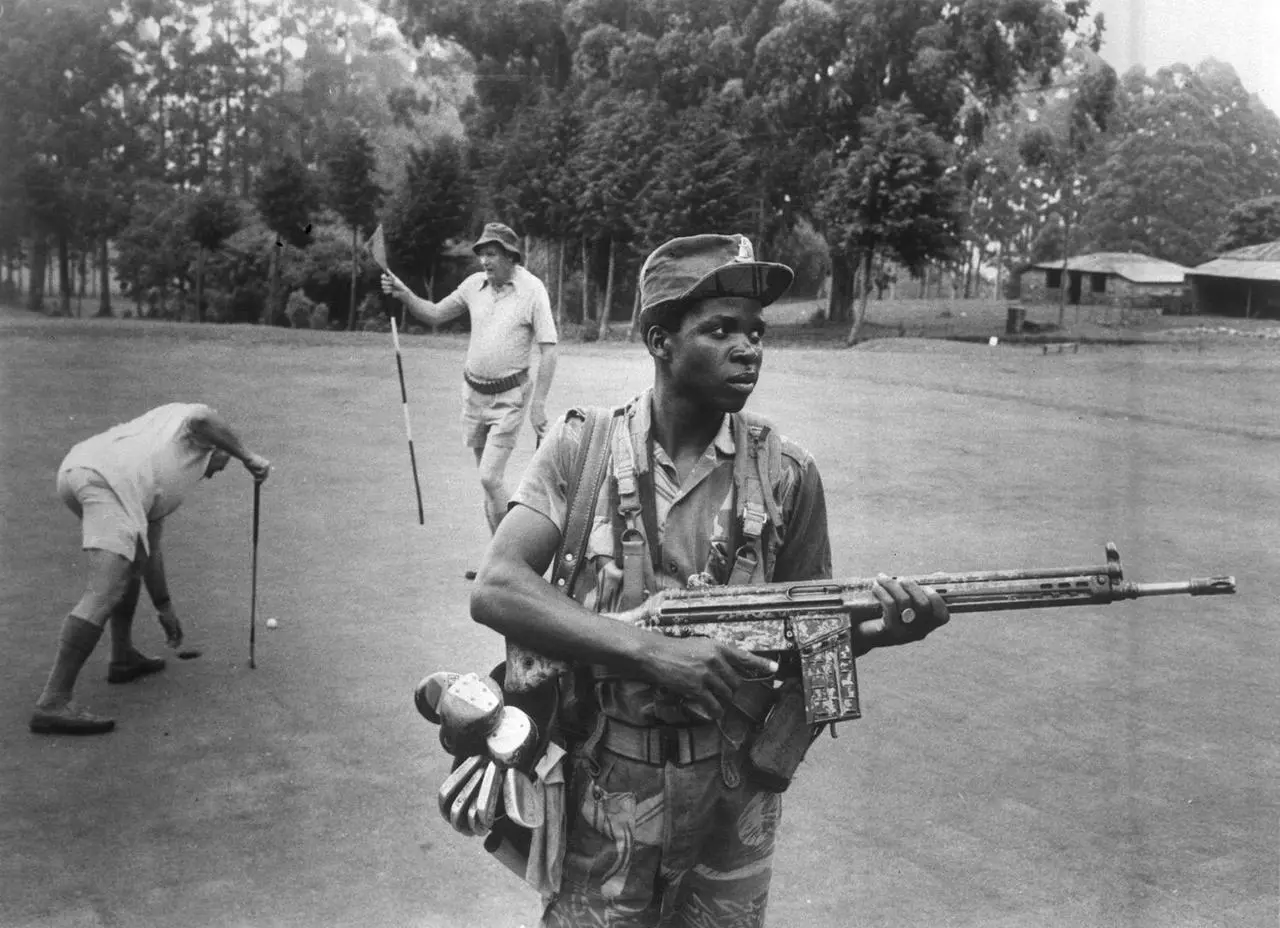

Apart from propagating myths about the national ‘community,’ the Rhodesians convinced themselves of many other fallacies or half-truths. They believed, for example, that ‘the best counter-insurgency force in the world’ was perfectly capable of defeating a contemptible army of ‘garden boys’.

In 1980 it was customary to argue that Rhodesia never lost the war but was ‘defeated’ at the conference table by devious British politicians.

These claims overlook the fact that the ‘garden boys’ were swarming over the entire country by 1979, and ignored the possibility of an eventual military defeat if the war had continued.

We thought we’d win because we were superior in firepower, and training. We thought they were bad soldiers. But they won. It doesn’t matter how and it doesn’t have to be militarily. The Rhodesian High Command really didn’t understand counter-insurgency warfare….you’ve got to look at it in terms of the people supporting the gooks. It does no good to justify it in your own terms. That’s just self- righteous. And that’s really what the Smith government was doing all along — looking at the African as a household pet. But he’s like white people and you’ve got to look at his motivation. That’s where the white government failed — in never really understanding the enemy or how to fight him.

American mercenary in Rhodesian army

Another favorite contention was that Rhodesia had ‘the best race relations in the world’. Any racial friction, like the war itself, was regarded as the creation of communist-inspired agitators who intimidated the ignorant, non-political black population.

Yet, for most Rhodesians the term ‘race relations’ was a misnomer; they did not ‘relate’ to Africans except as masters to servants, and few of them ever understood, or wanted to understand, the motivations of all those blacks who actively opposed white rule from the late 1950s.

Further assumptions were that Rhodesians were all rugged individualists, that they were imbued with the adventurous spirit of the pioneer column, and that they constituted one of the best educated societies in the world.

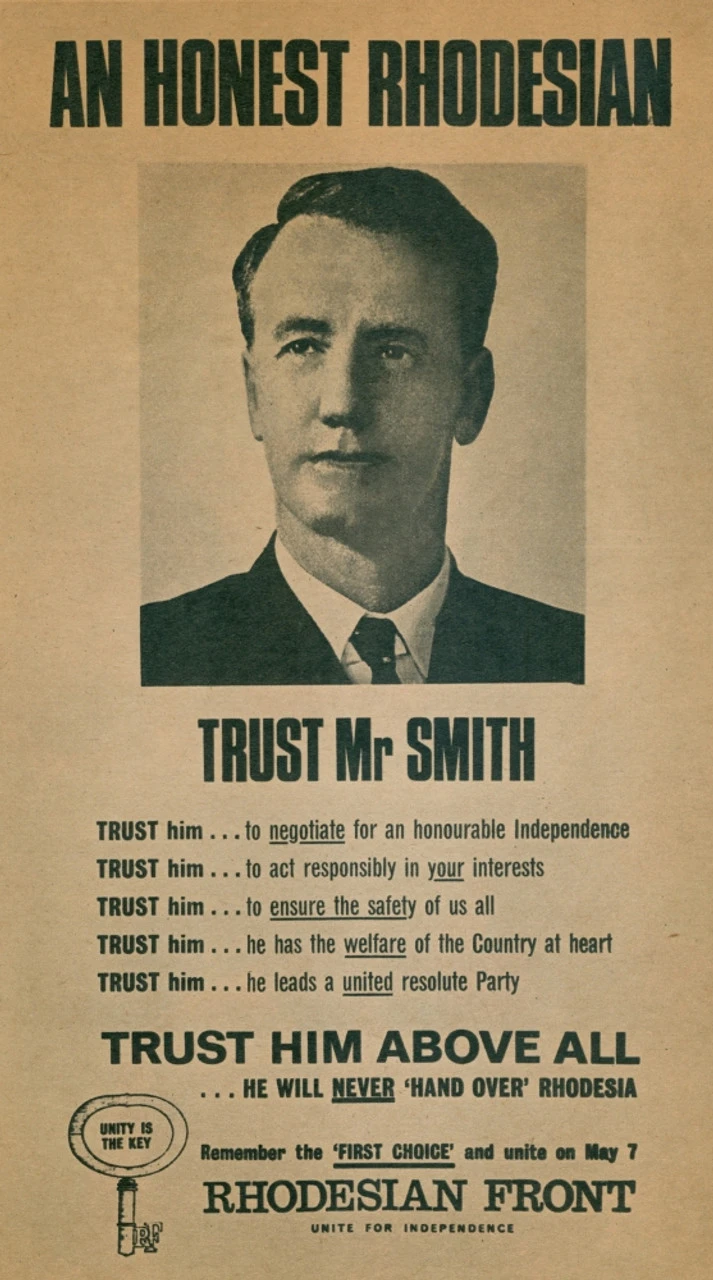

Yet successive generations had blindly voted for heroes rather than policies and then, lemming like, thousands followed their greatest hero – ‘Good Old Smithy’ – into the abyss. Fiercely independent, the Rhodesians were easily led, and even more easily deceived.

Often quarrelsome, they complained – all the time – but acquiesced in the imposition of an intrusive, all-embracing and stifling police state.

Above all, the Rhodesians liked to see themselves as forming one of the last bastions of western, christian civilisation. In reality, they practised a Sunday christianity in 1970; they yielded to moral temptation and, as the war progressed, they broke most of their own codes for civilised behavior.

The Rhodesians of the 1970s were less unified and more self-deluded than is often supposed. Throughout the 1970s the Rhodesians were preoccupied with the largely material needs, activities, and desires of people living in a semi-detached western society.

They spent more time – before 1977 – living their way of life than they did in defending it, and the lives they lived, and sought to defend, were remarkably ordinary. The big issues of social discrimination and majority rule rarely intruded into their daily business.

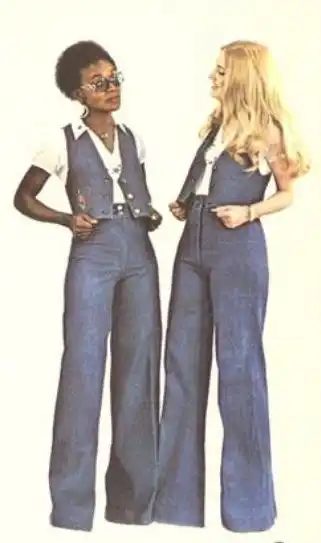

Rhodesian women, black and white, tend to be remarkably good looking. The Shona women have high cheekbones and fine features which make them exceedingly pretty, to European eyes at any rate. The whites have golden hair, lovely toast-coloured skin, and because of the weather, few clothes.

There is something particularly disconcerting about hearing those famous racist views expressed in that shrill mounting whine, coming from someone whose rounded figure is straining out of a thin nylon dress.

One such accosted us in a restaurant. "I heard you were journalists, and I've come over to tell you that Ian Smith is the greatest politician in the western world. He's so honest and straight. If the blacks could vote for him, they all would. He's the only reason we've had 14 years of civilisation."

The Guardian, 1980On 11 November 1965 (Armistice Day), the Rhodesian government made a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI), severing its ties with Britain, and the future was far from certain.

The Rhodesian Front government assured the waverers that UDI was not rebellion; it was merely a quarrel with a despicable Labour government in Britain and most British people were on Rhodesia's side.

It was poorly played propaganda but it had its effect, just as any propaganda has an effect if it says what people want to hear. And the Rhodesian man-in-the-street was not alone in his gullibility.

In the weeks following UDI Ian Smith was virtually inundated by tens of thousands of congratulatory letters from all over the world, mostly from Britain.

From being the relatively unknown son a butcher in the village of Selukwe in central Rhodesia, Smith had become a world figure overnight and a hero to millions.

Propaganda saw to it that the image of a 'strong, honest, simple man' was created; that his war-time experiences as an RAF pilot were made into a legend; and that he was portrayed as the 'saviour' of western civilisation in central Africa.

Mandatory sanctions were imposed on Rhodesia right after UDI, and no other country recognized it. Rhodesia was the first pariah nation, and was to struggle for some kind of recognition for its entire history.

Under the banner of the Rhodesian Front, the white nationalists gained nothing from this move; in fact, it came to mark the beginning of the end.

While most Rhodesians welcomed the event on that day, it truly was a great betrayal of everything that the previous generations had wrought, and it led to a brutal civil war that destroyed the lives of thousands.

Estimates put the number of war-related deaths on Rhodesian soil between December 1972 and December 1979 at more than twenty thousand: 7,790 black civilians, 10,450 guerillas, 468 white civilians and 1,361 members of the Security Forces (about half of them white).

BLAIR FRASER REPORTS FROM SALISBURY, APRIL 2 1966

At several anniversaries celebrating UDI, Prime Minister Ian Smith would sound the independence bell, but initial euphoria slowly gave way to a hollow clanging of despair.

In the months after UDI there was a wave of desertions from the BSAP. New immigrants left for personal reasons; immigration boards asserted that many left because they did not find the prosperous lifestyle promised by the brochures.

Three deserters arrested in early November simply said “Rhodesia was just not what we expected it to be.” Those who found their way to the Botswana border, sometimes in stolen vehicles, were taken to Zambia and then London, where they were required to repay their airfares.

Rhodesia modified its Citizenship Act in 1963 to allow it to issue its own passports. Britain would no longer provide consular services for Rhodesians; it was hoped that removing Rhodesian citizens from British nationality would protect them from charges of treason—which UDI was—when they traveled to the United Kingdom or Commonwealth nations.

New laws allowed immigration authorities to ban anyone traveling on a Rhodesian passport from entering Britain or to confiscate any passport issued by the Rhodesian government; Nevertheless, many officials in the Rhodesian government traveled on British passports.

Journalists noted how glum everyone seemed: instead of parades and celebrations the atmosphere seemed “menacing.”

TASTE OF PEACE ON VACATION LEADS COUPLE TO QUIT RHODESIA

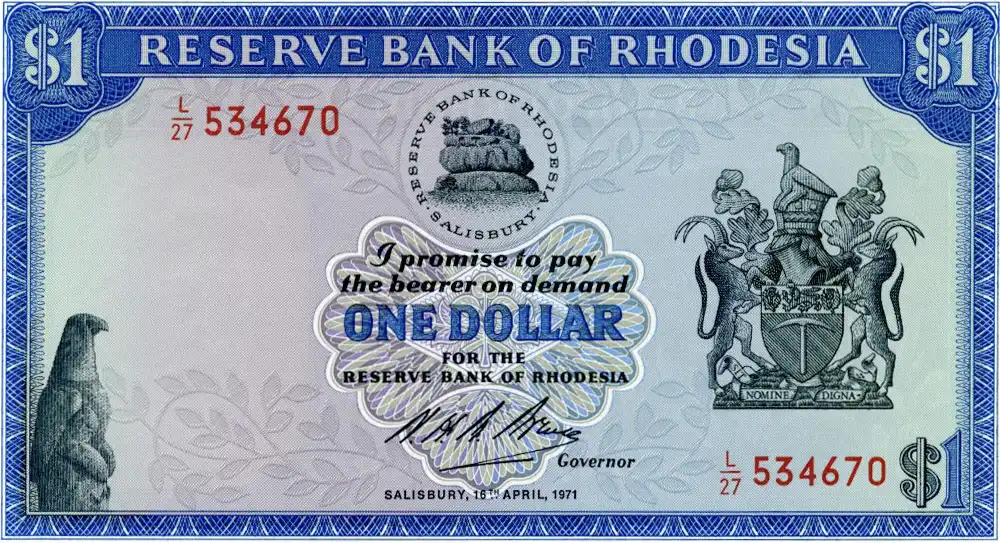

DEALING WITH DOLLARS

Even though the dollar had

been chosen as its name because it had an international

respectability—the U.S., Canada, Hong Kong, Australia,

and Taiwan all had dollars—the Rhodesian dollar was

polluted. Its very existence outside Rhodesia signaled

that illegal trade had taken place: no one wanted it.

Throughout the 1970s, as the guerrilla war intensified and as Rhodesia’s survival seemed in doubt, individuals sought ways to obtain foreign exchange. There were many stories of small and private currency violations.

Rhodesians sometimes bought foreign exchange from visitors or paid their hotel bills so that the equivalent would be deposited in foreign accounts.

The press reported two company directors who bought 1000 rands from a South African resident in Salisbury, a game warden and his wife who put the unused portion of their travel allowance in a bank account a friend opened for them in Pretoria, and company directors accused of exporting goods to South Africa and not repatriating their earnings from them.

Leading figures in the Rhodesian Front bred Brahmin cattle to export to South Africa: sales took place in Rhodesia for a modest price, and then the full value would be paid in South Africa, in rands.

Large currency violations were not reported in the press; the trials of those individuals who were found out were held in camera. The only place with detailed descriptions of the export of Rhodesian dollars is in Rhodesian fiction.

In Ginette a corrupt businessman gives his lover—an innocent and law abiding sales manager— instructions on how she can earn foreign exchange “by bits of paper.” Her task is to bribe the sales agent to produce two invoices, one for the company for the actual purchase price and one for the Ministry of Commerce and Industry at the inflated price. Once the Reserve Bank approved of this figure, the funds were remitted to Europe; the item was purchased for its true price, the sales agent was given 10 percent of the total, and the remainder was deposited in a foreign bank, preferably in Switzerland but anywhere other than Britain would do.

Ginette – Sylvia Bond Smith

Rhodesian dollars were so identifiable with the

rebel regime they could not be used anywhere else. In

fiction, however, they were given an international

value.

Guerrillas seeking to overthrow the regime needed to enter Rhodesia with sufficient local currency to meet their needs. Dealers in Johannesburg bought Rhodesian dollars, smuggled out in the checked baggage of businessmen and savvy tourists, at a discounted rate, smuggled them into Botswana and resold them at a slightly less discounted price.

The dollars eventually got to Zambia, where they were issued to the guerrillas operating in Rhodesia. No one in Zambia could purchase Rhodesian dollars because of sanctions and exchange controls.

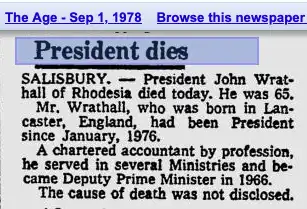

On 20 July 1978, during a session held behind closed doors, the High Court of Rhodesia convicted a group of Rhodesians of fraud. The court was told how the accused had salted away millions of dollars at the taxpayersʼ expense.

Reports in the 16 July editions of The Star mentioned that the accused men included Tim Pittard (Head of the Department of Customs and General Adviser), Rodney Simmonds (former RF Member of Parliament for Mtoko, District Commissioner and businessman), Norman Bruce-Brand (Under-Secretary in the Rhodesian Ministry of Defence), the chief finance officer in the Ministry of Defence, and Eddie Muller (of Rennies Shipping Agency).

Although the men were fined and ordered to repatriate all the stolen cash, the sentence did not include terms of imprisonment because imperatives of the state demanded that the procurement continue. Several of the accused were virtually indispensable because they alone had the right contacts in Europe.

While investigations into the scandal were under way, the Rhodesian public was shocked to learn of the sudden death of President John Wrathall. A terse communique announced that he had died in his sleep, but this official statement did little to stem ebbing white morale or to quash rumours that he was also implicated in the misappropriation of government funds.

When his body was found, a government physician was called, and he sympathetically stated that the cause of death was a heart attack. No post-mortem was held, and a burial was quickly arranged. Stella Day, doyenne of the Rhodesian press corps for most of the 1970s, stated that Wrathallʼs death was due to suicide, and Ken Flowerʼs daughter, Marda, recalls that her father came home that evening and told them of Wrathallʼs suicide.

A report appeared on the front page of the Sunday Mail that recorded the death as due to an accidental gunshot wound and that no foul play was involved. However, the death certificate was never made public, despite repeated requests from the media.

Calvin Trillin visited Rhodesia in early 1966. He was the first of many visitors to disparage what Rhodesians bragged about, particularly their working telephones.

He was told over and over again that telephone service was so bad in neighboring Zambia that businessmen preferred to drive hundreds of miles to the Copperbelt rather than wait for a connection.

Trillin saw something “constricting” about a country “where the national aspiration can be stated in terms of preserving an efficient telephone system.”

Rhodesia’s economic decline in the late 1970s was due to high oil prices, drought, war, and diminishing access to foreign exchange—problems that beset many African countries after 1972.

What made the downturn in Rhodesia more acute, was that it was war that was draining the country’s foreign exchange and manufacturing had saturated local markets.

There was a gradual decline in domestic investment. Shortly after the failure of a proposed settlement with Britain, Rhodesian economists observed the general feeling that “something always seemed to be going wrong.”

In 1969 Rhodesia produced a new constitution that pushed segregation to giddy and unworkable heights: its goal was not simply to create separate provincial councils for the three “races”—Europeans, Shona, and Ndebele—but to remove all rural Africans from participation in the institutions of representative government.

Such a constitution was impossible to implement, but it was adopted by the new republic of Rhodesia. In a few years the efforts of a war fought against two guerrilla armies, based in neighboring countries, took their toll.

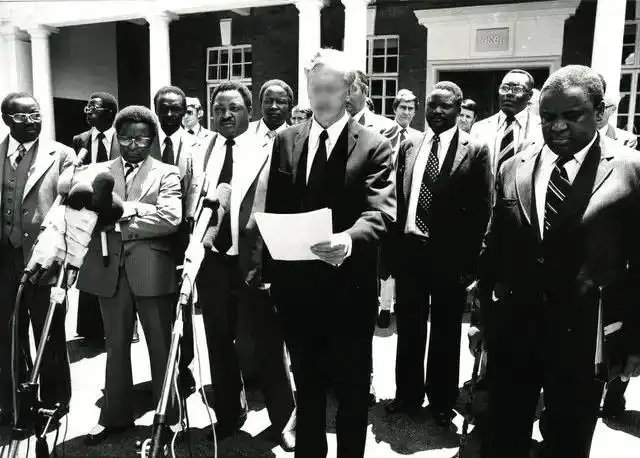

Rhodesian officials went to an all-party conference in Geneva in 1976, met with British and American diplomats throughout most of 1977, and eventually agreed to an “internal settlement” with a timetable to majority rule.

In early 1979 there was a multiracial government elected, led by the party that had organized resistance to the Pearce Commission, and with a new name, Zimbabwe-Rhodesia, which Salisbury wags and British journalists quickly changed to Rhobabwe.

The government of Rhobabwe, with Abel Muzorewa as prime minister, gave a freer hand to its military than Rhodesia had done and began to bomb the camps in Mozambique and Zambia.