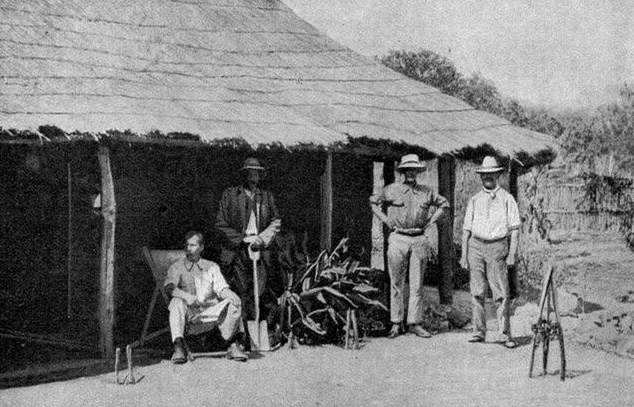

The African attitude towards the solitary Europeans who had made their appearance in Rhodesia from the 1860’s onwards was ambivalent.

On the one hand, many Africans appear to have recognised the technological superiority of the white men, and the Ndebele at any rate were aware that they were members of a larger tribe, which they respected for virtues not at all incomprehensible to a military nation.

Yet one cannot but be impressed by the way that many of the chiefs greeted their early European visitors—rather in the relaxed manner of a member of the aristocracy receiving a formal visit from a person of respectable but decidedly inferior social antecedents.

By the time that the Pioneer Column came through, many of the chiefs throughout Rhodesia must have received such visits. From the African point of view, whether Ndebele or Shona, the occupation of Rhodesia must have seemed like a Trojan Horse operation.

There was a sense of shock and outrage when it was realised that the character of these European visits had altered and that the white men had come to stay.

They intended, too, to break up all the old trading patterns and replace them with an economy which they controlled. And so the Shona attitude to the advent of the white people, in about 1892, began to change.

The story is told that on the morning after the whites had arrived and hoisted the famous flag at Fort Salisbury, they found a red ox tethered to the pole as a sign of welcome. But after some months, when the Pioneers had shown no signs of moving on, they found a black ox tied to the pole as a kind of delicate, but nevertheless emphatic, indication that they had outstayed their welcome.

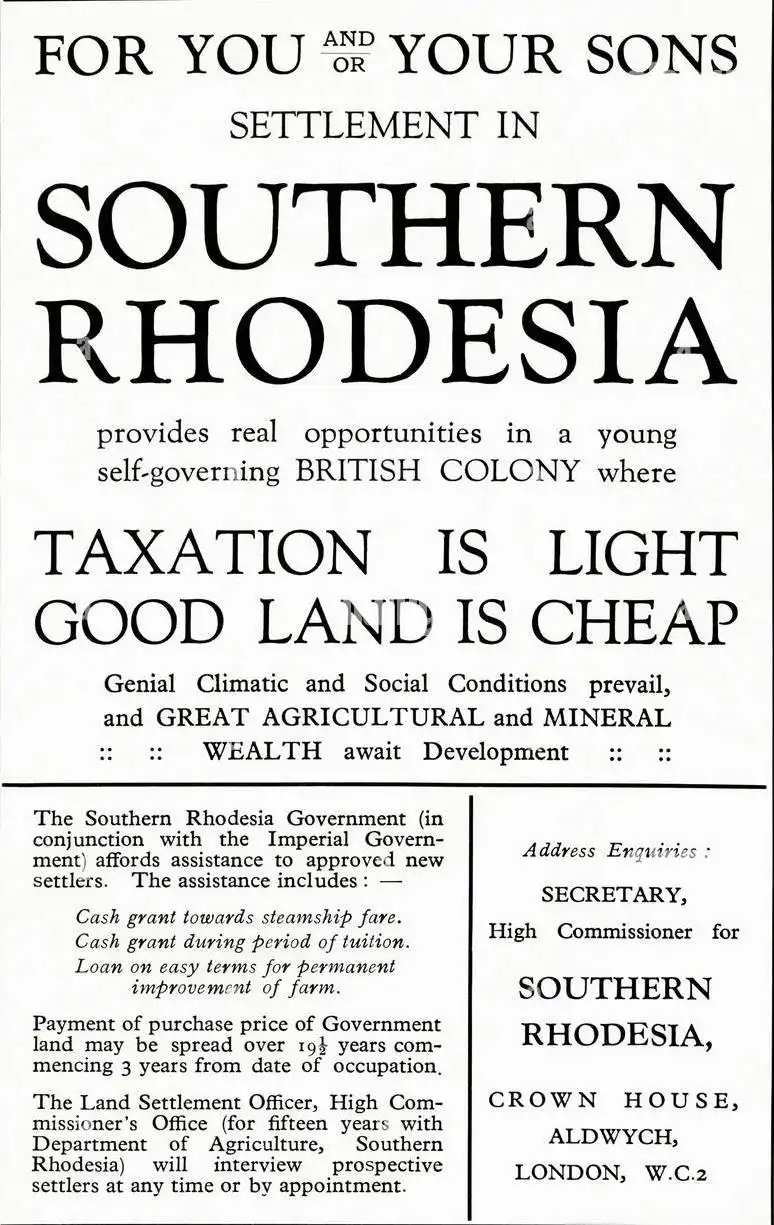

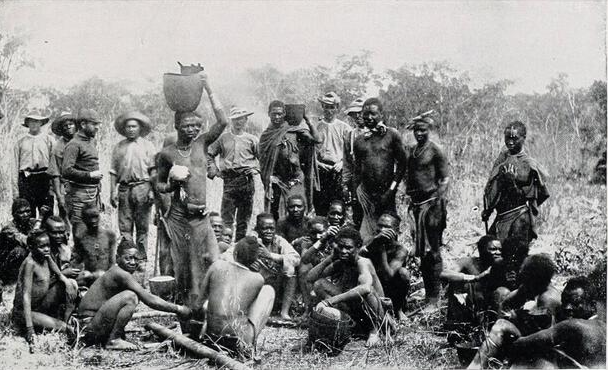

Not merely had the whites remained, quite ignoring such warnings, but they were now rudely interfering with African life on an increasing scale. For instance, they expected an abundant supply of labor and when this was not forthcoming, there was no thought of offering greater inducements to work.

In one instance an Inspector Bodle led a police patrol to a kraal because the headman had refused to send his men to work, saying that “his men were not going to work for white men and that if the police came he would fire on them“.

The headman was arrested and fined a considerable quantity of stock and given 50 lashes in the presence of men of his own and other kraals.

And there were, of course, some much more serious instances where there was considerable loss of life. Now whatever local Africans felt about the presence of white men in their country, most of the white pioneers were completely untroubled by the niceties of their constitutional position and regarded the country as having been taken over for their own benefit.

This attitude was expressed on occasion even by hostility to the Company when it attempted to bring about more order in relations between black and white.

One finds the position to be that a large European settler force was busy possessing itself of the choicest parts of Mashonaland on the basis of the fiction that this area was the territory of the Ndebele king who had authorised them to do so.

In the meantime the interests of the settlers were in complete conflict with those of the said Ndebele king whose actual relations with the area in question were those of a military parasite, alternately raiding its peoples and levying tribute by force.

The Shona, on the other hand, whether in the area subject to Ndebele influence or not, merely desired to continue their age-old way of life, which included a good deal of bickering among themselves.

White settlement brought about a show of unity among the Shona which the Ndebele raids failed to evoke. Despite all their outrages the Ndebele did not consider trying to change the way of life of the Shona, whereas from quite early times it was clear the Shona way of life and the European way of life were basically incompatible.

H.C. Thomson, a correspondent for The Times of London, captured the issue most succinctly at the time, when he heard that those resisting ‘preferred the Matibili rule to ours, because under them they were troubled but once a year, whereas now their troubles come with each day’s rising sun’.

The chief was reduced to a person lower than a constable in criminal matters and to the most inferior sort of civil magistrate whose every decision was open to appeal, often by men who could be chiefs’ grandsons in age and whose knowledge of tribal law was taken from one or two rather incomplete and erratic textbooks left by early Native Commissioners.

The chiefs’ mystical connection with the land was often shattered by imposed tribal movements, and the suspension of practices which were deemed to smack of witchcraft, the onset of Christianity, and finally the removal of his right of allocation of land.

This was transferred to agricultural authorities of the Government and it no doubt had a profound effect on weakening the authority of the chief over his people.

It is even less easy to sum up change in the field of family relations in a few words. The old forms continued to a large extent, but the goodness had gone out of them.

Generally, there was a weakening of all social authority, and with it a rise in the incidence of self-willed and antisocial behaviour. Social norms to a very major extent rely on the regulative aspects of community life, social disapproval, the quest for social esteem, and so on.

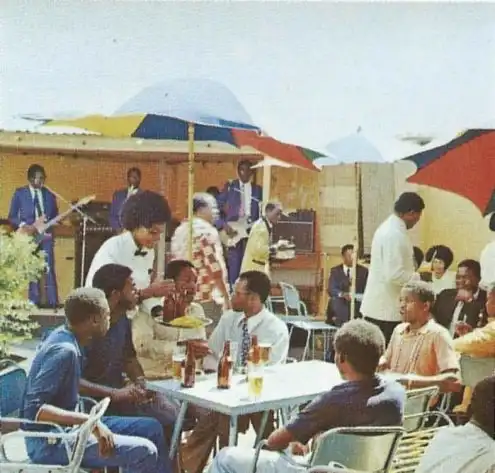

Labour migration broke the bounds of the tribal social order and residence for long periods of time in the vast human melting-pots that we call towns completed the bad work.

The influence of traditional concepts of the supernatural and practices associated therewith remained very strong. Africans simultaneously took to Christianity in a big way. The two were not incompatible in the eyes of Africans.

Curiously enough it seemed to be those Africans who adopted strange forms of Christianity, these forms with notable traditional elements, the people known as the Mapostori or the Amapropheti, who were not at all well disposed towards traditional African religion.

Some of the earlier observers underestimated the part that Mwari, the Shona high god, played in the culture of many Africans and that it was not very difficult for many of them to accommodate Christianity.

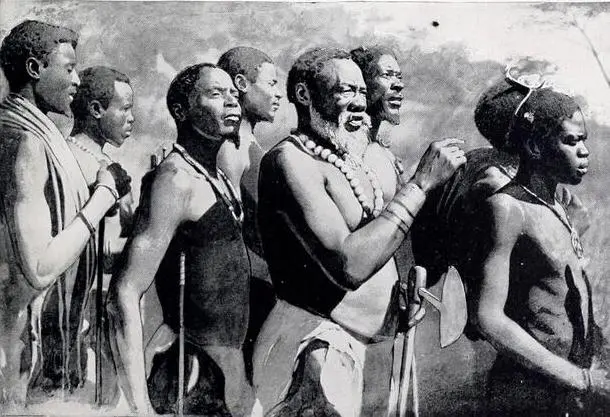

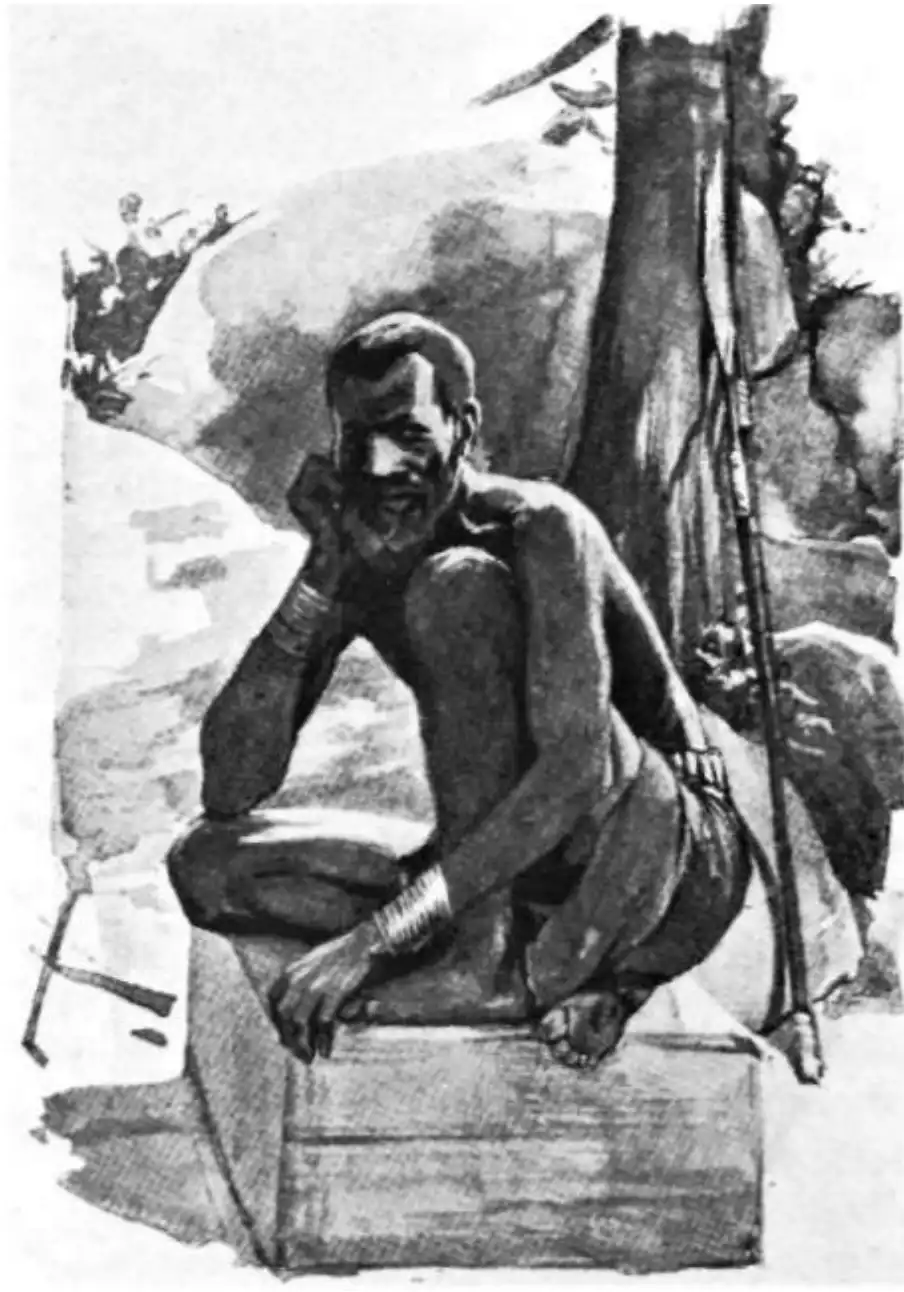

Mapondera—Chief of the MaKoreKore, 1893. Mapondera was a great warrior who happened to be out of the country at the time of the 1896 rebellion but came back soon afterwards and his tribe rose in 1900.

It was defeated and he fled into Mozambique. There he made contact with the Monomotapa and gained his support.

In 1901 he invaded Rhodesia at the head of a large KoreKore force, and marched on Mount Darwin with the intention of killing all the whites living there.

He clashed with a force of Police which eventually scattered the KoreKore. He was captured and died in gaol during a hunger strike.

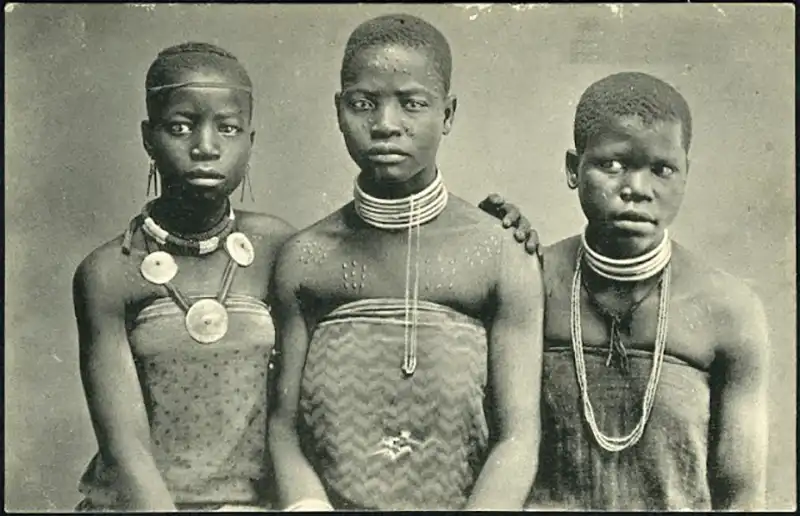

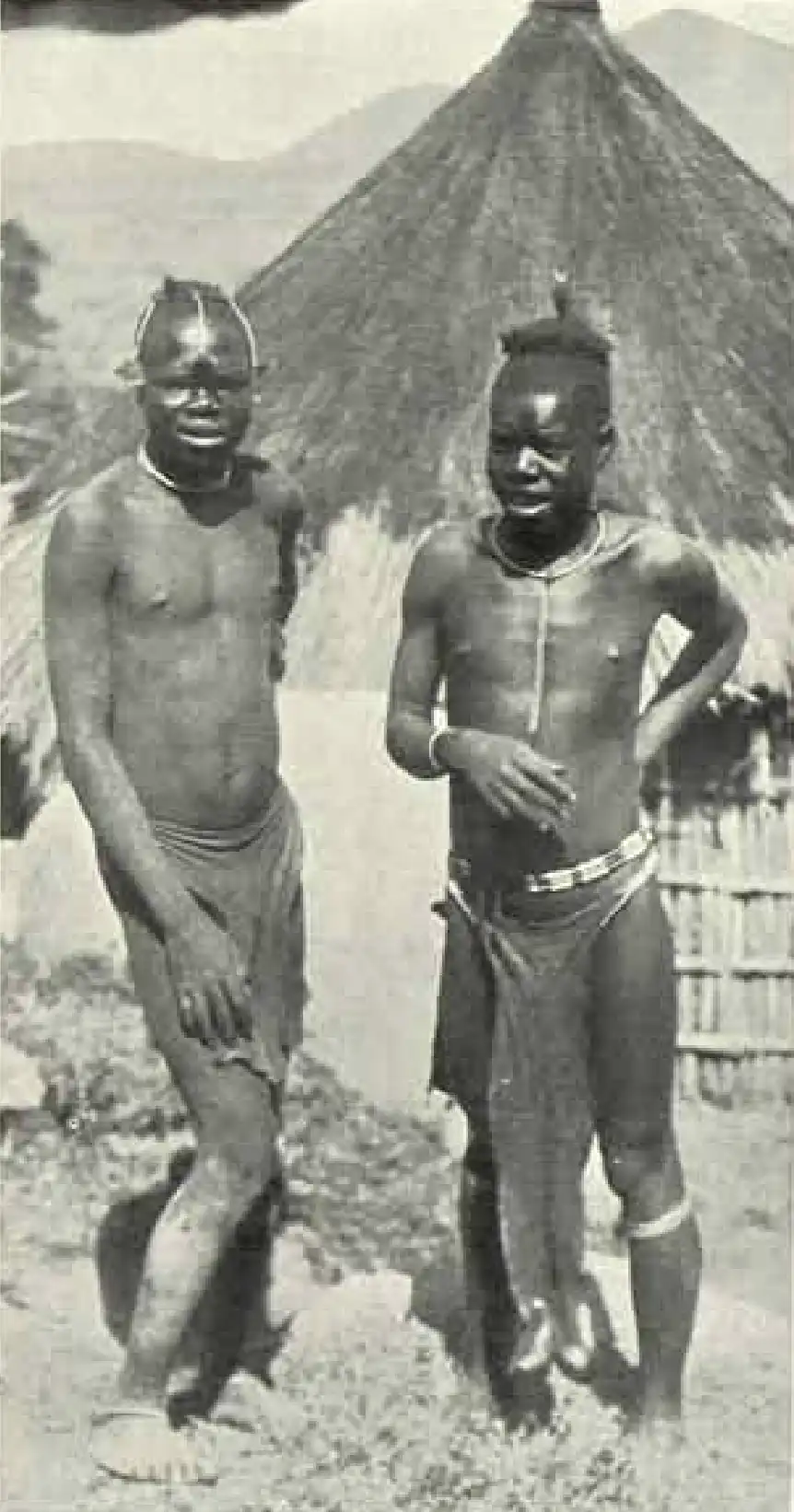

THE MASHONA

The Living Races of Mankind

The only important tribe in the British South Africa

Company's territories south of the Zambezi which has

survived the Matabili invasion is the Mashona.

Thanks to the abundance of safe retreats among the granite hills of their country, they have escaped the partial extinction that has befallen their neighbors and cousins, the Banyai and Makalaka; but they have been so greatly reduced, that, though they occupy 100,000 square miles of territory, they only number about 200,000 persons.

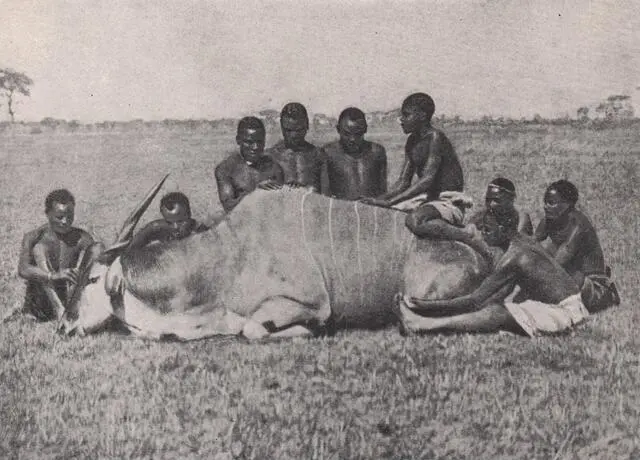

The Mashonas are peaceful and industrious; they are laborious agriculturalists, and raise large crops of grain, including maize and rice. They keep herds of small cattle, flocks of goats, and large numbers of fowls.

Their houses are circular thatched huts, which are perched for safety in the least accessible places on the kopjes or granite crags: for the Mashona were weaker than their enemies the Matabili; and as they had no military organisation, but lived in small communities under local chiefs, and never combined for defence, they had no chance of successfully resisting the Matabili raids.

The Mashonas are skilled smiths, and make excellent iron assegais, battle-axes, and hoes. They play a musical instrument like the marimba of West Africa: the Mashonaland form of this "piano" conntains twenty iron keys on a small board, which is placed inside a calabash to act as a sounding-board.

The Mashonas kill elephants either by hamstringing them when they are asleep with a broad-bladed axe, or by stabbing them between the shoulder-blades with a very heavy assegai from an ambush in a tree.