During the first decade of the 20th century, it came to be realised that the earlier hopes of finding a second Witwatersrand were merely an illusion; but such hopes lived on. The end of the Anglo-Boer War was followed by a mining boom, but this collapsed during the financial crisis of 1903-4.

As a direct consequence of this, thoughts turned to the potential wealth of land; and an awareness grew of the important role the African agricultural sector had assumed in the economy and the threat it posed to the future labor supply of the Colony.

By 1908, when the white agricultural system began to expand, African agricultural opportunities gradually began to be reduced.

In order for white agriculture to be promoted, African agricultural competition had to be eliminated. The BSA Company began to charge rents to Africans living on unalienated land (land that had been appropriated but not yet sold by the BSAC), and a rent of £1 per year was levied on all Africans living on such land.

NCs were told to warn natives that they must either move into reserves after the crops had been reaped or be prepared to pay the rent.

If Africans chose to move into the reserves, many would be forced to relinquish the ability to sell surplus agricultural products because of the general remoteness from markets of these areas.

Those who chose to remain on white owned land came to play an important role in the development of nascent white agriculture. On occupied white farms, the landowners could exact rents or labor services from their tenants, and they could also charge grazing and dipping fees; thus they were not only contributing financially to white agricultural development, but forming an all-important labor force.

Those living on unalienated land were also welcomed as a source of revenue to the BSA Company. The government at this stage made no effort to evict Africans from the land because the white sector was still heavily reliant on African agricultural production.

The charging of rents to Africans residing on white land had the desired results, and from 1909 the rate of migration of Africans from white areas accelerated.

The proportion living in reserves increased from 54 per cent in 1909 to 64 per cent in 1922, and at the same time the rate of African production began to decline as poorer and more densely populated land was brought under cultivation. Thus, of necessity, many Africans were forced to seek wage labor.

The consequences of this policy were to have a greater impact on the Shona than on the Ndebele. The latter were used to paying rents and preferred to remain on their traditional lands in order to do so, rather than move into reserves.

In Mashonaland, however, there were fewer Africans in alienated areas – furthermore, many reserves were in close proximity to both mines and white farms and Africans were still able to market agricultural surplus.

As white farming developed and the marketing of African produce was discouraged, the Shona increasingly realised the necessity of seeking wage employment which, after many years of acquiring cash through sale of agricultural surpluses, they were reluctant to accept.

As early as 1903, one NC was heard to have said,

I am strongly in favor of abolishing the large Native Reserves and in lieu thereof giving them individual title on the quit rent system. If this were done it would facilitate the labor question to a certain degree; whereas at present the natives living in these reserves cultivate as much ground as they please, the products which are in excess of their consumption and the large remaining surplus they sell to traders in order to meet their hut tax and by this mode of living the average Mashona does not require to look for work.

If a native owned a limited piece of land which would only produce sufficient grain for his own consumption he would be bound to go out in search of employment in order to earn enough money to pay his tax

Experimental farms were opened and extension facilities offered to white farmers. In 1912, a Land Bank was set up making credit available to persons of European descent only. The Bank gave loans of up to £2,000 for the purchase of farms, livestock and agricultural equipment.

NAR N3/6/3 NC Makoni, 1903

It was obvious, even in the absence of restrictive land policy, that with such assistance the white farming sector would soon surpass that of the African sector.

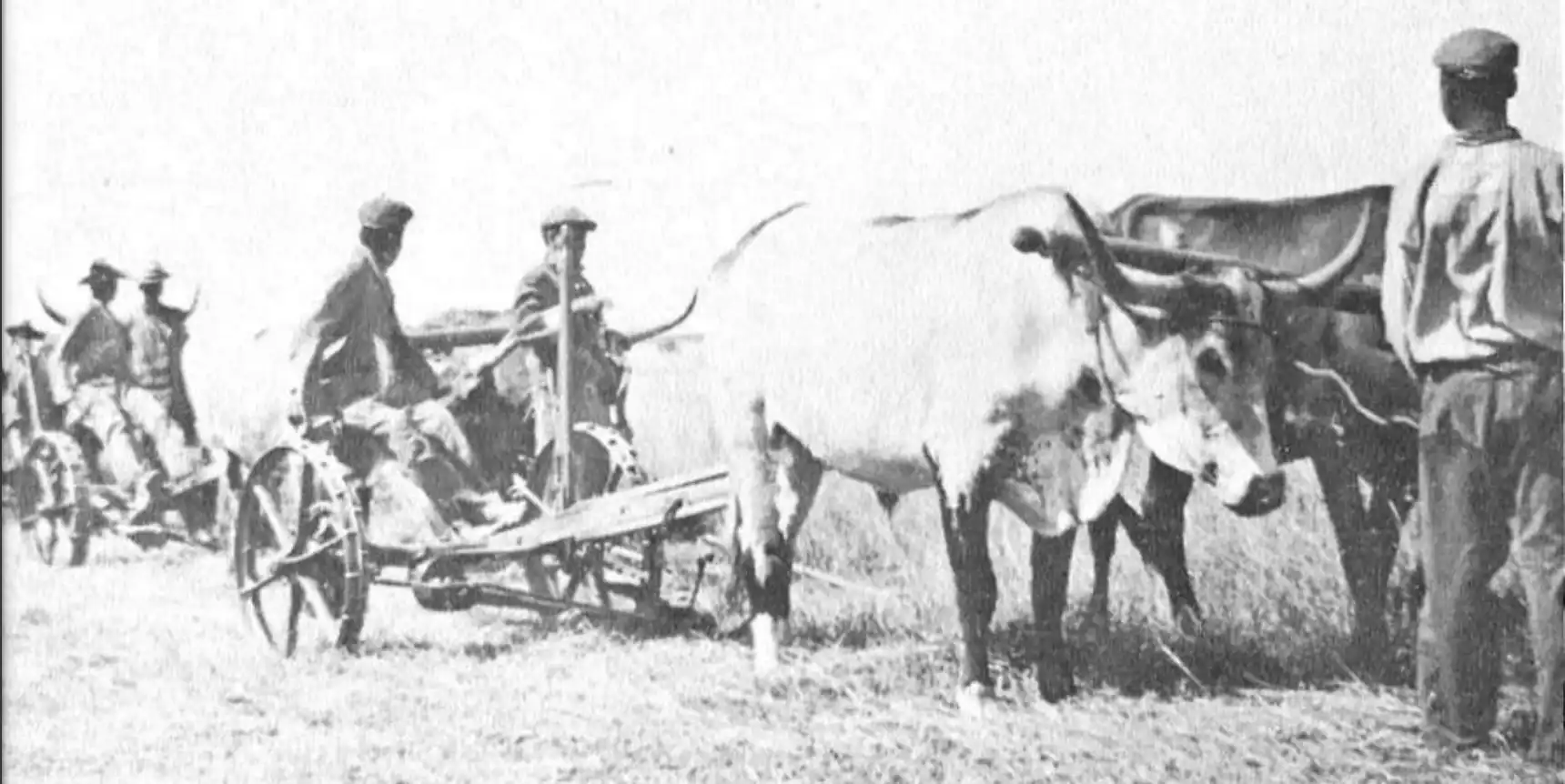

The cattle industry expanded from the base provided by African cattle.

African cattle have been found to make an excellent foundation, being extremely hardy and immune, or nearly so to many diseases of the tropics, qualities which are transmitted to aconsiderable extent to their graded descendants … Matabele cattle have served as a valuable foundation on which the European farmers have, by the use of bulls of British breeds, built up their present excellent breeds.

E.A. Nobbs, Director of Agriculture, Rhodesia Agricultural Journal vol 18, 1921, pp 258/9

The white cattle industry continued to expand on the base of African cattle, which were purchased at very low prices, particularly in times of drought and famine.

Once the herds of white farmers had reached a moderate size, the prices offered for African stock decreased markedly and the last source of income available to the African, other than that of wage labor, dwindled.

In the south-west, all cattle were sold or killed in the famine of 1912. The old men are paupers, while the younger men are away at work.

NAR N3/11/1-3 Ndanga 21/8/1915

When maize began to be grown in abundance in the gold belt area, it had the advantage ‘of having both the best soil and easy access to markets in the mining centres. African markets in this area were thus taken over by white farmers.

In addition, as the tobacco industry expanded with its preference for light sandy soils, many Africans in Mashonaland lost access to the land which they had traditionally cultivated. The expansion of the white cattle industry at the same time as that of the African, resulted in increased competition for grazing lands.

The whites began to challenge Africans for markets, cattle and land, beginning what was termed the squeezing-out process.

Prior to 1914, white farmers had not forced Africans off their land. If they chose to leave through pressure created by the imposition of taxes and other devices, they were free to do so, but whites were reluctant to force their eviction because at this stage they supplied crops, labor services and also revenue through fees and rents.

By 1914, however, competition for African labor between the mines and the farmers had increased. To complicate matters, white farmers required seasonal labor at precisely the same time that Africans planted their own crops, and they were reluctant to work for white farmers during this period.

To achieve the twin goal of both reducing African competition which had become a larger threat during the war years, and discontinuing the general refusal of Africans to work, white farmers began imposing higher rents, grazing and dipping fees on their African tenants.

Such action, it was hoped, would force more Africans into the reserves which were further away from the main markets. In this manner, both goals were achieved: competition was of necessity reduced, and Africans were forced to seek wage labor because of their inability to realise a sufficient cash income through the sale of agricultural surplus.

The natural consequence of this movement of increasing numbers into the reserves during these years was the acceleration of congestion in these areas. Access to markets was denied them owing to the remoteness of many reserves from the main centers of economic activity.

African crop production began to decline, partly as incentive waned with diminishing market potentials, and partly as the practise of extensive methods of agriculture became increasingly difficult to execute under congested conditions.

Furthermore, cattle numbers increased rapidly during this period, placing more pressure on the land, and incentives to dispose of this surplus through sale deteriorated with the collapse of the cattle market in the 1920s.

An additional consequence of the slump in the early 1920s was that many Africans moved into the reserves, having no incentive to pay rent when sale of produce was being uneconomic.

Having made this decision to migrate to reserve areas, future possibilities of gaining financial requirements through sale of crops was negligible.

Thus, whilst for white fanners the slump was merely a temporary downward trend in the business cycle, for the African this situation was, in many ways, irreversible.

The instability of white agriculture in the late 1920s and the simultaneous increase in their political power, gave rise to a great deal of aggression towards Africans living on white land.

The white farmers, if they could not achieve satisfaction through the framework of government aid, were more determined to achieve security through other means. The form these desires assumed were pressures for segregation.

The main pressure for segregation, then, came from white farmers who sought to consolidate their position, for although they were the main pillar of economy in the 1920s, their position was by no means secure.

The main reason for this was the lack of a viable staple crop, hence they still had reason to fear competition from the Africans who were also cultivating maize, and who, if given an opportunity, could do so at far lower cost of production than could whites.

They were also alive to the fact that should Africans purchase land in their midst, with easy access to markets and the availability of good quality soil, their potential as competitors would be vastly increased.

White farmers were also aware that the possibility of Africans purchasing land in their midst was becoming a more feasible proposition as their earning capacity increased.

The white farmers were the largest sector demanding segregation; nevertheless, they were supported in this field by the missionaries. The missionaries were opposed to Africans coming under what they considered, in many cases, to be the corrupt influence of the white sector of the economy.

Initially, the missionaries were of the opinion that Africans were “uncivilised barbarians” who must be civilised at all costs.

By the 1920s, however, they came to realise that there were many aspects of tribalism which were worth preserving. The missionaries were of the opinion that attempts to assimilate Africans into the white economy before they were ready, would result in their adoption of many of the less desirable aspects of the white sector.

With the passage of the Land Apportionment Act, white farmers had achieved their objectives. Africans were prevented from purchasing land in potentially good farming areas, and they were pushed into areas remote from markets.

Furthermore, the clause giving Africans a six year period in which to move into their own areas ensured the acceleration of congestion therein, the consequent cessation of agricultural competition and the concurrent necessity for Africans to seek an alternative source of income through wage labor.

It prevented wealthy Africans from purchasing land in areas in close proximity to white fanns, and the Purchase Areas ensured that there would be no conflicting interests with whites: their access to both railways and markets was restricted.

Over half of the purchase areas assigned, lay on the borders of the country, and approximately 4,000,000 acres of the total assigned comprised five large, remote, low-lying, tsetse ridden areas in Darwin, Melsetter, Bubi, Bulalima-Mangwe and Gwanda

R.H Palmer, Land and Racial Domination, pp. 182/3

Segregation retarded the African’s development but in some ways that was its purpose. Reserves were neither served by roads nor given sufficient agricultural extension advice or to technical services provided to Europeans. Through segregation Africans were entrenched in primitiveness.

D. J Duignan, Native Policy in Southern Rhodesia, 1961, p. 307

Disruption of the Africans’ traditional agricultural system began with the arrival of whites, although the manifestations of this were not apparent for at least two decades.