The police, rather more than most institutions, reflect the community in which they work. The most vivid example of the deterioration of white society in Rhodesia is provided by the change in the attitudes and the methods of the British South African Police, as the Rhodesian police was called.

Until 1945, and particularly in the period between the wars, the police had largely been recruited in Britain from middle class families. The Force attracted adventurous young men and the most honorable service was in the outposts of the Empire.

For the most part the men who joined were by the standards of the day ‘officer material’. There was very little serious crime in Rhodesia, and their relationship with the white community was easy and familiar.

Although essentially a gendarmerie and trained to operate as a fighting force, they were, except on the rarest circumstances, unarmed when on duty.

Especially in the rural areas, where a young man might be responsible for keeping the peace in an area of several hundred square miles, they were even respected by the Africans towards whom they showed the arrogant affection of the paternalists they were.

After the war recruits were chosen from a wider variety of classes, but until UDI the majority still came from Britain, or from the British element in Rhodesia, and maintained the easy going traditions of their predecessors.

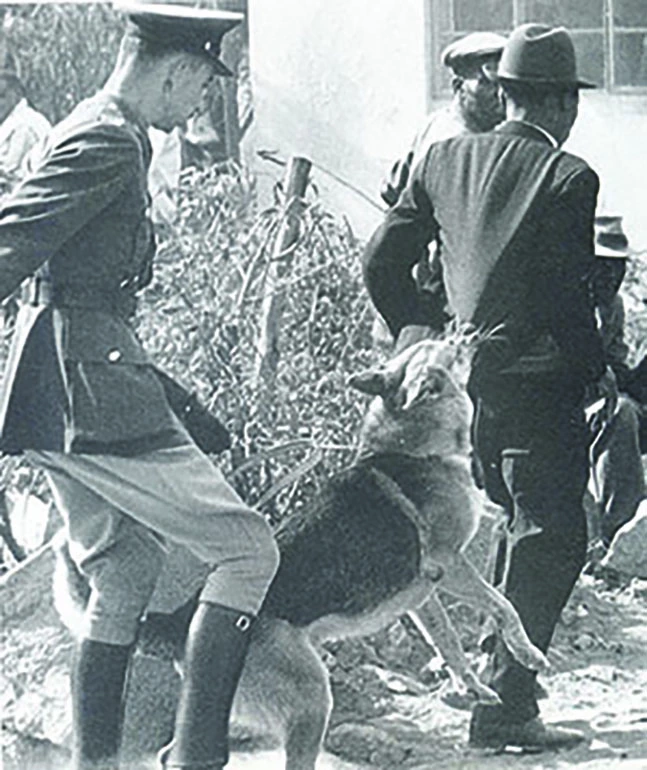

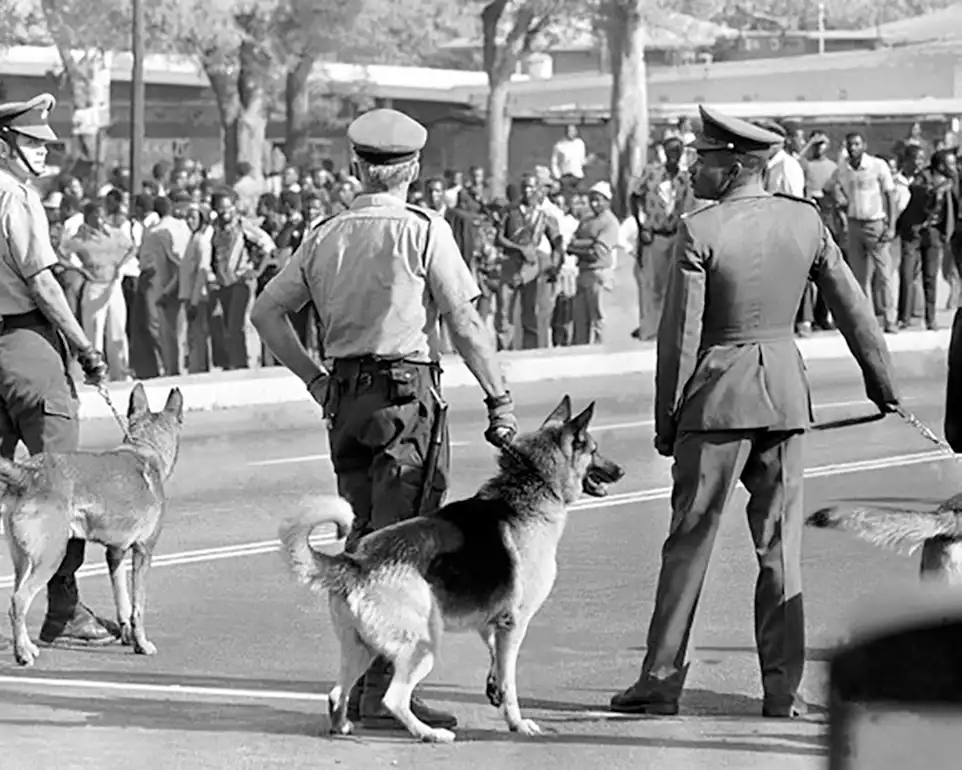

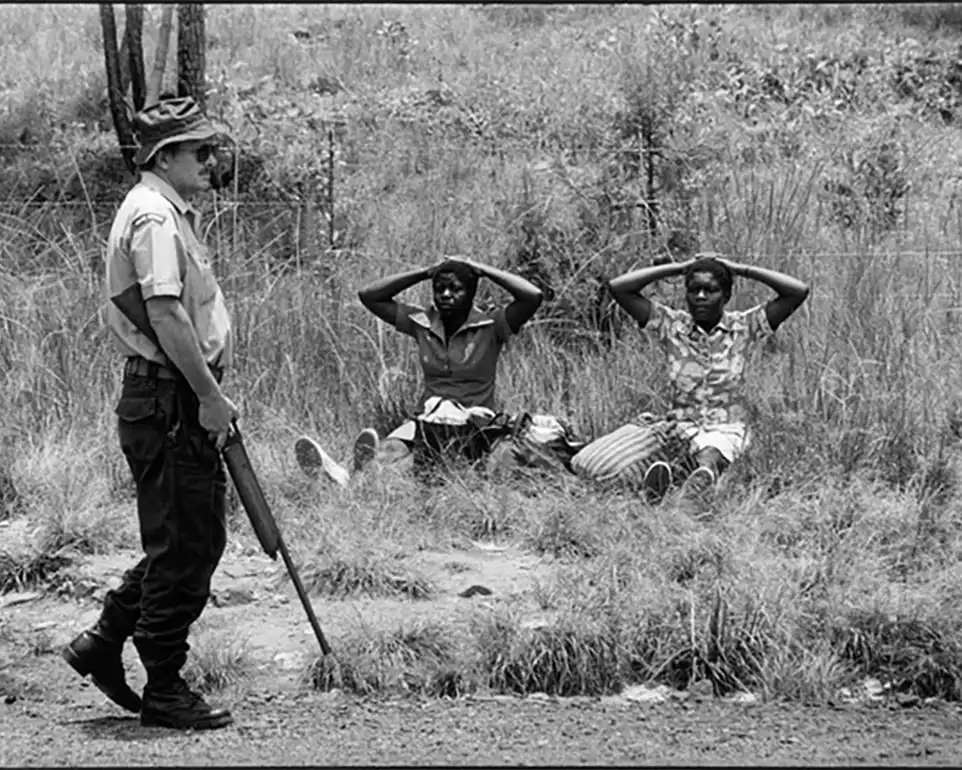

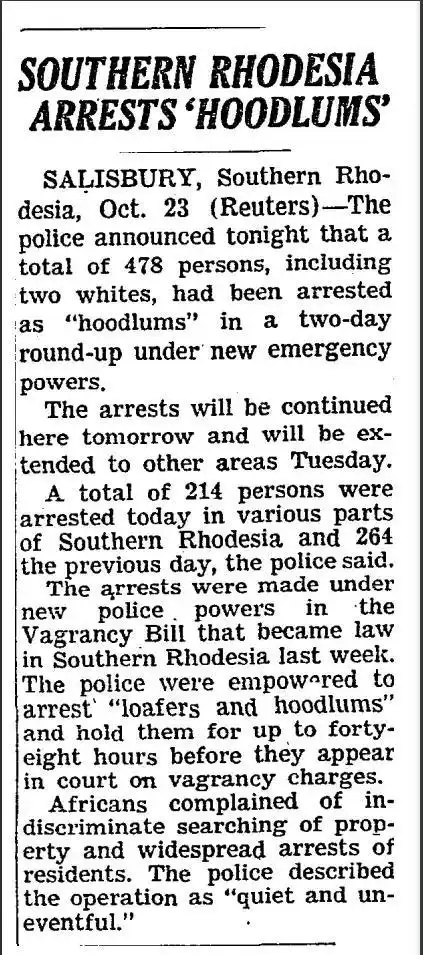

Not until 1960 did the Rhodesian police find themselves using firearms against African mobs and from then on feelings of enmity developed between them and large numbers of the African population.

Not only did the use of violence in controlling and in clearing crowds become frequent but the intimidation and ill-treatment of prisoners and witnesses spread.

It is notoriously difficult to obtain proof of police malpractices where the Force itself conducts its own investigation into complaints, and the courts in Rhodesia were reluctant to accept evidence of ill-treatment.

However the Rhodesian courts began to show concern at the number of alleged incidents referred to them, as when eleven out of thirteen charges against Ndabaningi Sithole were dismissed when Crown witnesses complained they had been beaten to give evidence.

In closed meetings with the police before the 1962 elections, Rhodesian Front candidates assured them of greater support for their efforts in dealing with African nationalists, and, as it was intended to be, this was taken as approval for the use of less orthodox methods.

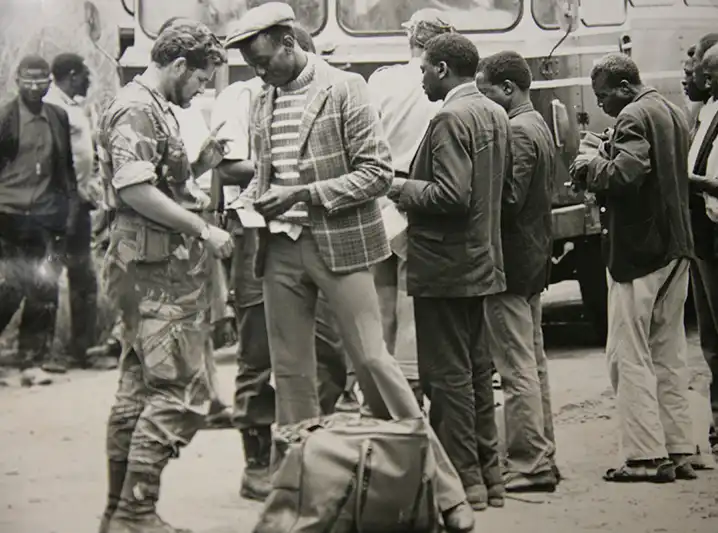

The police were given a free hand, especially in the African townships around the urban centers, to harass, arrest, detain and interrogate any African, and their attitude became harsh and aggressive.

Several senior officers admitted with regret that the standards of police behavior had declined but, far from denying that intimidation took place, they justified it.

The lack of cooperation they received from a passively hostile majority of the Africans made it increasingly difficult for them to obtain evidence of ordinary crime, let alone political offenses.

A man might be seriously injured in the presence of a score of eyewitnesses, none of whom would admit to having heard or seen anything.

Gradually the police became the agents of white hostility rather than of white control and, by all but a few members who maintained the old traditions, the Africans were regarded as an enemy to oppress rather than as wards to be protected.

Although strong measures were taken against white political opponents of the regime, there were no instances of brutality or violence.

There was much of the mild intimidation practised by security officers everywhere, such as the ostentatious photographing of demonstrators or brief detention for questioning, but none of the harassment which became the lot of Africans.

Informers were widely used against white dissidents, just as they were in the African areas, and Europeans who were not entirely committed supporters of the Rhodesian Front became wary in their relationships with people not well known to them.

The situations deteriorated very rapidly after UDI, opposition to which was regarded as grounds for police surveillance. No one knew who to trust and dinner party conversations were carefully related by informers and filed with the police records.

Under censorship no discussion of, nor protest against, police methods was possible, but it is fair to say that they were widely enough known among the whites and that the European community as a whole approved of such methods as opposition became equated with disloyalty.

The more the party became identified with the state the more the police became the servants of the Rhodesian Front rather than the impartial guardians of the law, and more and more of their resources were directed towards the suppression of opinion rather than the prevention of crime.

So far as the European was concerned, however, the most effective pressures were those applied by the community itself. The crowds attending election meetings in 1962 were noisy and offensive in their language and their behavior deteriorated in the years which followed.

Roy Welensky, at a by-election in September 1964, was howled down by an abusive throng whenever he tried to make a public speech.

People who attempted to heckle or even to question Ian Smith were beaten over the head, had lighted matches and other small objects thrown at them, and there were occasions when individuals were roughed up after meetings.

On no occasion were serious injuries inflicted or weapons used.The rare student and other protest demonstrations would be jeered at by a few persons but the general reaction was cold hostility and contempt.

In no community are there many individuals with the moral courage to resist popular trends and even less when nonconformity is regarded as betrayal of society rather than a mere eccentricity.

The prevalence of informers, the extension of censorship, the social and economic ostracism which was imposed combined to separate the opposition, not only from the community at large, but also from each other.

Relatively few were able to endure the sense of being surrounded by a completely unsympathetic public, and either withdrew from any discussion or limited all their contacts to the handful of trusted friends who shared their views.

Considering the relative mildness of the intimidation to which white “resistance” was subjected, its behavior must seem to be one of contemptible timidity.

For a number of reasons such a judgement would be harsh, especially coming as it often does from those who have no experience of living in a hostile society which not only resented criticism but approved the suppression of it.

What makes a true Rhodesian? He blindly follows, he gullibly believes, he patiently suffers. Should he resent or dare to express a different opinion, he is un-Rhodesian. He must accept every word uttered by Ian Smith and all his ministers. He must remain in Rhodesia, fight for Rhodesia, pay for Rhodesia and become a political and financial prisoner

Letter from one E. Conway. The Herald July 25 1978,

APARTHEID

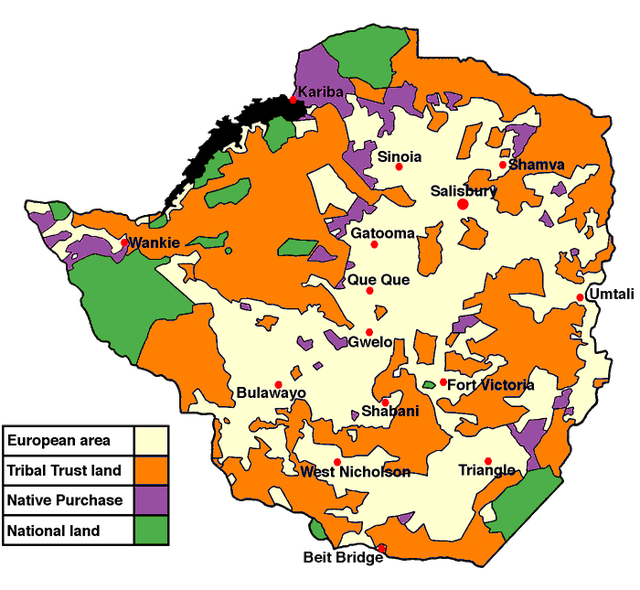

The Land Apportionment Act of 1930 divided Rhodesia into

four sections: the African Areas, the European Areas,

the Forest Areas, and Unassigned Land which was to be

allocated later.

The mineral resources and major transport networks, including all the railways and tarred roads, were carefully confined to the European Areas as was a large part of the fertile land with good rainfall.

In short, those areas with geographical and economic advantages were concentrated in the “White Area”.

The Act was the cornerstone of white supremacy in

Rhodesia and provided that:

(a) No African shall acquire, lease or occupy land in

the European Area

(b) No owner or occupier of

land in the European Area, or his agent shall

(i)

dispose or attempt to dispose of any such land to an

African

(ii) lease any such land to an African

(iii)

permit, suffer or allow any African to occupy any such

land

Some exceptions were made: the principal one was to enable whites to have resident black domestic servants.

Section 43(d) permitted occupation if the African was employed by the person who owned or lawfully occupied the land (usually a European) but only for so long as his employment necessitated his presence upon the land.

An African was permitted to occupy European land if he was undergoing instruction at an educational institution established for Africans and situated on European land, or if he was receiving treatment at a hospital or clinic situated on such land.

These exceptions themselves illustrate how rigidly the policy of segregation was enforced. African occupation of European land was restricted to these sharply delineated exceptions, and the purchase of European land by Africans was expressly prohibited.

The case of the Tangwena people illustrates the brutal methods employed by the Rhodesian Front government to implement its policies of racial separatism under the Land Apportionment Act

PROPAGANDA

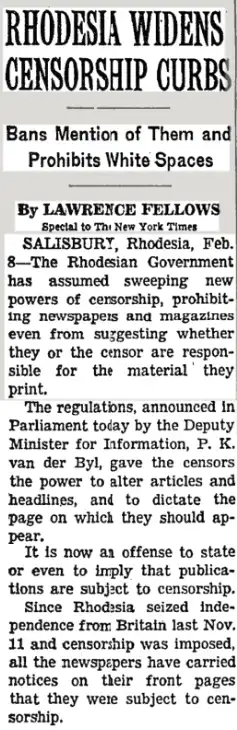

If it is true that a Press can only resist suppression to the extent that the public will support it in so doing, the position of radio and television services is even more vulnerable, as Rhodesian experience again proved.

The Rhodesian Broadcasting Corporation was modeled on the BBC in that it was controlled not by a government department but by a Board of Governors.

Until Ian Smith took office there had been frictions and disputes between ministers and the corporation, as to the type and extent of the coverage given to news and current affairs, but the independence of the RBC had always been respected.

The Rhodesian Front had always argued that because of the hostile Press, the Government should have special facilities on radio and television for counter-propaganda.

Ian Smith decided to use broadcasting as a government agency and his first step was to create an appointment, new to Rhodesia, of a Parliamentary Secretary (junior minister) for Information, to which post he nominated P. K. van der Byl.

There was in existence a government information department responsible for the distribution of ministerial speeches and Press statements, government reports and the like, as well as for providing facilities to visiting journalists. The Director was an established civil servant.

Van der Byl brought from South Africa a man called Ivor Benson to act formally as his adviser but who was, in fact to take control of the information department and turn it into a propaganda machine for the Rhodesian Front which, in his mind, was indistinguishable from the Rhodesian Government.

Ivor Benson was a journalist, right-wing essayist, anti-communist and racist conspiracy theorist who was preoccupied with variants of the theme of a hostile world conspiracy.

He wrote speeches for Ian Smith and other ministers in which this fantasy came to be regularly expressed, with the embellishment that a prime task of the conspiracy was to overthrow the Rhodesian Front.

The BBC, the World Council of Churches, Wall Street and the Kremlin combined with other, on the surface similarly incompatible, allies to achieve this end. Fanciful as these propositions may appear, the methods adopted to ensure their uncontested promulgation were severely practical.

Under Ivor Benson’s direction, the Information Department was re-shaped to disseminate the material prepared with his guidance and in line with his theories. Any dissidents among the staff were invited to resign or were dismissed.

New recruits were placed on contracts rather than on the civil service establishment which made their removal easier if they, in their turn, proved not to be amenable.

With the source of Government propaganda organized, the next step was to control the channels through which it could reach a wider audience than party zealots. Step by step the broadcasting corporation was turned into an instrument of party propaganda.

The board was reconstituted with political adherents and Helliwell, a nonentity who had played no part in Rhodesian public life, was appointed chairman. The absorption of Rhodesia Television into the propaganda machine followed.

Rhodesia Television and the programme company, International Television, operated under license as a commercial enterprise. The contract between the companies and the Federal Broadcasting Corporation had, after the break-up of the Federation, been extended for one year and was thereafter allowed to continue pending re-negotiation.

By September 1964, van der Byl had decided to buy out the commercial interests on the government’s own terms so that television would come under the detailed supervision of the already subservient RBC. in justification, Ian Smith said

We have got to ensure that such a powerful medium as TV does not fall into irresponsible hands, the hands of people who may be the enemies of the state

A glimpse of the real issues was revealed when RTV announced that the government had demanded control of the television news services as one of the conditions of the company being allowed to continue under any form of contract.

In the face of bitter and widely publicized protests, the company was unable to resist a government determined to take it over, and television in Rhodesia became subject to the same tight direction, and was required to show the same subservience, as sound broadcasting.

The services were thus used to advocate Rhodesia Front policy and the expression of any conflicting point of view as gradually eliminated.

The television screen and the broadcasting studio became reserved for those individuals who either supported or agreed not to be critical of any issues which the government and the party decided should be removed from debate.